Meditation In A Killing Field

What is the relationship of Buddhism to genocide?

We were sitting on bamboo mats in a dark pagoda built at the site of a former Khmer Rouge killing field on the highway from Siem Reap to Angkor Wat. Our Cambodian guide was struggling through a recitation on the life of the Buddha depicted traditionally in murals on the walls and ceiling. “Bodhi tree there, Buddha he enlighten, eightfold path. . .”

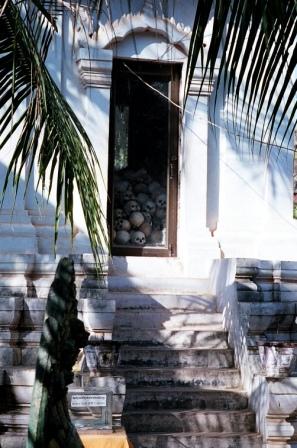

I watched a monk who had been sleeping on a canvas cot in a cool place by the altar shuffle to a doorway. He stood in the bright frame searching the folds of his saffron robe for something – a pack of cigarettes. He looked depressed. The guide was getting the eightfold path wrong. “Right talk, right think, not steal and lie, right sexual. . .” I focused my old Canon SLR. The monk stood smoking in the light, looking out toward the killing field with its plain monument, a windowed box half full of human skulls.

What was this monk thinking?

They came in from the countryside, teenagers of dull and hateful countenance, according to the French ethnologist Francois Bizot who traveled with them. Between 1975 when they took Phnom Penh and 1979 when Vietnam-aided exiles took it back, Pol Pot’s Khmers Rouges emptied the cities, slaughtering 1- or 2-million bourgeois agents of “American imperialism.” (Bizot’s quote. The U.S. had conducted a secret war including bombing in Cambodia and Laos.) Prisoners were examined for stigmata (weak eyesight from reading, soft hands and feet, pale mark from a wrist watch) in places like the guest house next to the pagoda. They were taken out to the killing fields and shot or hacked to death. Monks too.

What was the purpose of a pagoda next to a killing field? Our guide had answered that it eclipsed the past. But he also had said something about ghosts haunting this strip of the prime real estate (35 luxury hotels have been built in the five years, by coincidence, since “Lara Croft And the Tomb Raiders” was filmed at Angkor). “People they fear, hear in night voices crying,” our guide said.

This stop in the tour was a surprise. We had scratched out Phnom Penh because its main attraction seemed to be the local killing field. It’s an old story. “The Killing Fields,” the movie, dramatized it. Journalists, even the sophisticated travel writer Pico Iyer, visited and told the story. The New York Times magazine illustrated it with prison mug shots of the condemned. Samantha Power’s “A Problem From Hell” dwelled on it and how the rest of the world stood by in ignorance (the same lack of hard facts that led Noam Chomsky and other liberals to voice support for the Khmer Rouge).

And now that it’s famous the government has privatized the Phnom Penh killing field. Since last year it has been under lease to an exhibition company from Japan that promises to preserve it in exchange for profits from the entry fees. There is money, so to speak, in the killing fields near every city. They are part of a tourism package built around the Angkor ruins, now visited by 10,000 tourists a day at $40 a head for a three-day pass (and the revenue goes to the government, not to preservation). So I wondered if tourism is why the government is attached to its genocidal past and if so is this a form of denial?

The government. It is defined by the CIA as a multi-party democracy. The CIA has no classification for a corrupt democratic junta. There is indeed an opposition party, but its leader had to leave the country or go to jail on charges of criminal defamation of Prime Minister Hun Sen. Then the king, strange king like his father, pardoned him. This new king, Norodom Sihamani, with his Western education and his love of UNESCO programs and his Buddhism, could be a surprise. His father, Norodrom Sihanouk, skilled and popular but also a professed communist in the time of the Vietnam war, might have saved Cambodia from Pol Pot if America had let a communist monarchy be instead of installing Lon Nol.

Or maybe the setup here, pagoda by a killing field, was just simply a Buddhist thing – like the Mahayana practice of meditating in a grave yard. Tibetan temples in Nepal are full of horrors, reminders of universal suffering, and the traditional Tibetan Wheel of Life is in the grips of Yama, god of death. By contrast the temples in Thailand, which like Cambodia is Theravada Buddhist, may be surrounded by scary devils, apes, dragons and Chinese warriors, but the statues are outside, not the inside. You get the impression that Theravada is inspired by the life the Buddha while Mahayana is inspired by the deep metaphysics of emptiness.

But these may be too-fine distinctions. For a Westerner, one question covers everything, and it is posed at the Siem Reap killing field, it is posed by Tibet, it is posed by the mass murder near a U.S. Air Force base in Arizona where two local teenagers in August 1991 dressed up in military gear, grabbed their guns, went to a Buddhist temple in the desert, lined up nine people including six robed Thai monks, and killed them all — executed them with rifle shots to the head, one by one. The question: What is the relation of Buddhism to genocide?

The armed Buddhist is a modern contradiction. In Thailand in the 1960’s, U.S. advisors to the Thai military encouraged a program called “de-Buddhafication,” I have heard, because young men with monastic education did not make good soldiers. They could not kill. The Japanese military junta in the 1930’s established Shinto as the state religion because, obviously, you don’t send armed Buddhists out to conquer the world. Where I live, the “Free Tibet” bumper sticker has survived Tibet itself, but often it is seen on the same Volvo with a “No War” bumper sticker. How are you going to free Tibet without war? How can you meditate with an M16 in your lap?

Still, there have been armed Buddhists in the past. The tiny kingdom of Bhutan remained free because its monks were fierce warriors, and they still are excellent archers. (Where I live there’s a small Bhutanese community which has an active archery range outside its sanctuary.) The Japanese classic “Tale of the Heike” is about warring monasteries in medieval Japan. And Americans loved the “Kung Fu” TV series in the Sixties (martial arts monk takes out gunslingers), but, sorry to say, it was fiction, as the idea of just and virtuous people shooting down planes with bows and arrows or fighting tanks with swords is fiction. But wait. . .

Here is a non-fiction: in Hue, Vietnam, our guide there stopped during a walk through a temple complex at a window that revealed an old car. A sign told how on June 11, 1963, the monk Thich Quang Duc drove the light blue Austin from there to a square in Saigon where he doused himself in gasoline and set himself on fire in protest of repression by the American-backed South Vietnam regime. Our guide pulled an 8-by-10 photo from his clipboard: the famous shot of the monk seated in the flames so stoically dying. The photo was on front pages and the evening news world wide, and it registered an otherwise ignored dissent. The world reexamined the nature of the “colonial bourgeoisie” (Frances FitzGerald’s term) regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, especially after his sister-in-law and surrogate first lady, Madame Nhu, referred to the self immolations as “monk barbecues.” These events may have changed the mind of President Kennedy because that November, two weeks before he was shot, the Catholic Diems were assassinated, and the military coup could not have happened without American complicity.

The martyrdom of the monks in Saigon was not strictly on behalf of Buddhists, but in the name of the people. As our communist guide in Hue explained, there by the blue Austin, Diem ordered soldiers to shoot protesters of any kind. Terror was the issue. Buddhism did not emerge renewed after the war. Communism and religion (“opiate of the people”) don’t mix. The communists have pretty well drained China and Vietnam of their long tradition of Mahayana Buddhism.

The South Vietnam government was not of the people. The Diem-built presidential palace in Saigon stands as it was in 1975 when the Viet Cong walked in. There is a U.S. escape helicopter on the roof, a U.S. radio transmitter in the basement bomb shelter. Visitors are shown the palace’s gambling casino, movie theater and ornate formal reception rooms. It was the fortified seat of a government defeated by a resistance begun by Ho Chi Minh, who lived alone in a simple house on stilts by a Hanoi pond, where fish came when he clapped. They still do. . . .

In the dark pagoda the young guide was winding up his speech, trying to remember the English for the Four Immeasurables (loving-kindness, compassion, joy, equanimity), which he claimed were represented by the four faces on each of the dozens of mysterious towers we had walked among in the central Angkor ruin called The Bayon.

The Four Immeasurables. Tsoknyi Rinponche, the relatively young Tibetan Buddhist from Nepal who has a devoted following where I live, presented them in a teaching a year ago as a progression that begins with the recognition of kindness. This Buddhist path has little traffic in the political world. What the Dalai Lama simply calls “the good heart” is ridiculed on talk shows as naiveté or weakness. The withdrawn holyman on his green mountain is suspected of cowardess in political rhetoric. He is derided in sexually explicit routines on the Comedy Channel. The political-industrial complex demands proof of strength in kindness.

Martyrdom is strength. That’s why “The Passion of the Christ” was a box office success. It drew evangelical Christians who generally avoid movie theaters. The message was, Christ died for your sins, and don’t you forget it. Catholics have always had the stations of the cross and the crucifix to remind them. The evangelicals with their stripped-down crosses needed a movie. Not that the tradition of Christian martyrs – and there were many – who refused to betray their faith should be forgotten, any more than the Saigon monks who died to send a message to the world should be forgotten. But there’s more to religion, or ought to be. Liberalism can’t forever justify itself solely on the existence of terror. When you are obsessed with your enemy you run the danger of becoming like your enemy. There is something to be said for putting the memory of past suffering to rest, just as the Vietnamese have gotten over “The American War.” I mean, Mel Gibson looks a lot like Cambodia.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama has not sold the legacy of fear or terror, although he might have done so convincingly. He is not obsessed with evil. The Tibetan diaspora has engendered a new and wonderful Western faith that, it seems to me as a wayward traveler, has left behind the wrathful devils that haunt the empty old monasteries of Nepal. As a journalist I covered the Dalai Lama’s visit to Santa Fe some years ago. He was asked if he hated China. He responded gently after a thoughtful pause that of course he did not. He said, on the contrary, “You learn from your enemies.” That, it seemed to me, is neither a denial nor an escape. I suppose it reveals an enlightened relationship to terror in the world — a refuge rather than a cohabitation.

As we left the pagoda I put palms together and bowed to the depressed monk, who, having finished his cigarette, was sitting on his canvas cot. He nodded slightly. In Thailand and Cambodia monks do not return the “wai” gesture, which is subject to cultural rules involving the social status of who bows first and deepest. Monks do not bow. Not even to Americans. Not even to the king. There is some hope in that.