Commentary On A Shooting At Nangpa La, A Pass In The Himalayas

Life In An Economy That Has Displaced A Culture

The death of a Tibetan nun shot down from a distance by Chinese riflemen on Nangpa Pass casts a long shadow from a very high place. It’s a specter of the Cultural Revolution at a time when China is showing more tolerance of religion.

Thousands of nuns live and practice in remote areas of the Tibetan Plateau. The Pundarika Foundation of Crestone, Colo., tells their story. Guided by a few aged survivors who came out of hiding, younger nuns are trying to preserve ancient lineages in a hostile world. They are threatened by loss of traditional support as their agrarian families are lured to the cities by promises of industrial jobs. The Chinese government seems to ignore them rather than persecute them. And this is hopeful. But the climber video of the Sept. 30 incident is not.

It shows a line of distant dark figures against the snow. They are trudging upward toward the pass – slowly because the elevation is nearly 19,000 feet and they have been walking for many days. Suddenly shots can be heard and the figures scatter. Two drop. One, later identified as the young nun, Kelsang Nortso, never gets back up. An intercut shows a rifleman taking position and firing. Later Chinese border police, armed and in uniform, come to the base camp where the video was shot. They have prisoners – frightened, downcast Tibetan children.

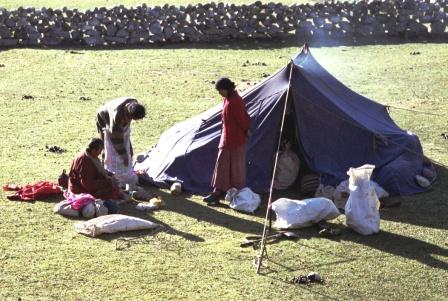

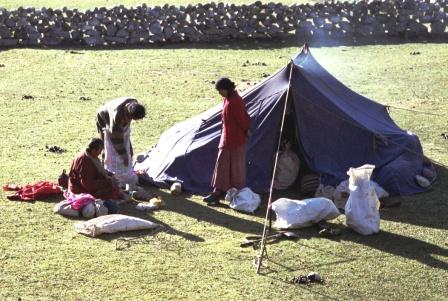

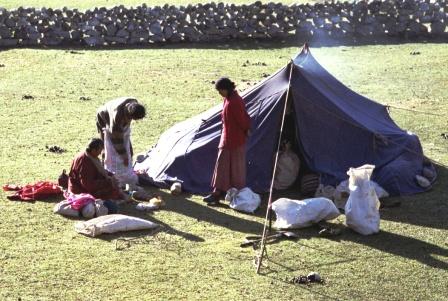

Watching it and reading the resulting news reports evoked memories of a caravan we encountered in the village of Thame in the Everest region of Nepal in 2002. The Tibetans had just come down from China and they were the first to cross Nangpa La (La, literally “high,” means pass.) that spring. There were young adults resting on a field-stone fence, children playing, a babe in arms. I asked – without words – to take pictures and was refused, vehemently. I saw defiance, not timidity, not fear. In the pasture by the fence some traditionally dressed women sorted out trade goods in a large canvas tent circled by browsing yaks. Taking pictures did not bother these older women. Why did it upset the people by the fence?

The news coverage of the Nangpa La shootings suggested an explanation. I recalled that the pass, which is about three days up the Bhote Valley from Thame, is an ancient trade route – so ancient that it is supposed to have been how the Sherpa people of Nepal migrated from eastern Tibet at least 500 years ago. In another day the caravan we saw would be in Namche Bazaar, a trekker-climber gateway known for its weekly open air market. The caravan was going to the market, where you can buy everything from dried meat and red curry to cases of Chinese Pepsi and cheap electronics. The thing is this: the Chinese don’t stop the yak caravans, which go down to Namche and return.

But Nangpa La also has been the escape route, according to the International Campaign for Tibet, for thousands of Tibetan refuges. The Chinese obviously are now trying to stop them by deadly force. The ICT says further that Tibetan refugees caught in Nepal are arrested and sent back. We saw a lot of armed soldiers in Namche and at checkpoints along the trail, out hunting Maoists. Some of them harassed our Sherpa guide. (The King’s army is made up mostly of Hindus from the lowlands)..

It occurred to me that the group by the fence in Thame more than four years before were refugees. That would explain their defiance. They were not obviously monks or nuns, just ordinary people with a fierceness in their eyes. I began to wonder what kind of nation would support international commerce on the one hand and the shooting of unarmed refugees on the other? I mean, why is the export of goods OK but the export of ethnicity a threat? It is ironic that Tibetan Buddhism has multiplied in exile.

The conflict is larger than Communism vs. Buddhism. I suspect it is part of a worldwide clash between economics and culture, between modernism and dwindling traditional ways of life. An illustration is the film just out on DVD, “Mountain Patrol: Kekexili,” which dramatizes the true story of a group of volunteers who set out to save Tibetan antelope from a wealthy pelt-poacher whose shooters mow down thousands of the endangered animals with automatic weapons. It should not surprise you that the “capitalist” gets the government’s tacit support, relative to the ethnic Tibetans.

A few years ago I went through an MA program that included intensive reading of Chinese classics. A classmate who later went to China as a teacher of English, the language of global commerce, told me, “The things we studied – Confucius, Lao Tzu, the Tang Dynasty poets – my students don’t know them. All they care about is English and science.” It’s sad to see a proud nation cut down an old and diverse forest and put in a parking lot – replacing spiritual values with political economy. And this goes for the United States as well.

The pavement can always be cloaked in tourist illusion. In this way the Chinese government preserves the Potala in Lhasa as a sort of museum and allows some public display of religion, I have heard. But in reality the government, as Nangpa La made clear, gets upset when its spiritual pets try to run away.