The Builder Governor

Remembering Jack Campbell

By Larry Joseph Calloway

Jack M. Campbell / The autobiography of New Mexico’s first modern governor: as told to Maurice Trimmer with Charles C. Poling, University of New Mexico Press, 2016.

I was lucky to arrive in Santa Fe before its style, real estate and cultural conflicts went commercial and while Jack Campbell was still governor. The city has changed, and people like Campbell usually decline to run.

I also was lucky to meet Maurice Trimmer on that first day as a New Mexico political reporter. After working for UPI in several big city bureaus, I had requested this transfer to a smaller pond, but now I was totally lost. Santa Fe looked foreign. The Bataan Building did not look like a state capitol. The governor’s office looked deficient with a staff of only seven, including Trimmer, the press secretary.

Perhaps because he too had been the new UPI guy eight years earlier, Maury sympathetically began some on-the-job education. He invited me to accompany the governor to El Rito. The state under Campbell had started a vocational program there to make use of what was irrevocably designated as a teacher’s college in the state constitution. We saw young men and women learning hair styling and construction and auto mechanics.

On the drive back to Santa Fe in the limo the director of the new Board of Educational Finance said it would be logical to move the school from the rural village to the town of Espanola. The governor said, “Bill, your problem is you try to apply logic to Northern New Mexico.”

Next, Trimmer told me there would be room on a flight to inspect Fort Bayard in the Anglo southwest corner of the state near Silver City. There was indeed room. The only passengers on the twin-prop state plane were the governor and me, side by side. All I knew about him was he was raised in Kansas by a widowed mother, that he had been an FBI agent before joining the Marine Corps and that he had seen some brutal combat as the leader of a rifle platoon in the Pacific war zone. He did not look like any of those people. He looked more like an honest lawyer in a suit, which he was.

At Fort Bayard we were met by some local folks who took us on a tour of what began as a cavalry fort and became a veterans’ home that the federal government wanted to abandon. The state under Campbell had just acquired it for a regional treatment center. The group were saying grateful goodbyes on a porch as the governor was leaving. He motioned to me, saying, “Come over and hear some of this wisdom.” I took a note for a story.

On the flight back to Santa Fe, Campbell read True magazine, sometimes laughing and telling me what it said. True’s slogan was “the man’s magazine,” and it had cartoons and adventurous stories told with manly humor, but no girlie pictures. Tony Hillerman, who also began his New Mexico career with UPI in Santa Fe, wrote for True before it folded in the era of Playboy.

The Campbell autobiography, released last June, is written in the modest style of True. Trimmer was the primary author in close collaboration some 20 years ago with Campbell. Charles Poling, a freelancer and novelist who also wrote the memoirs of the late Gov. Bruce King, was engaged to fill a gap in the narration.

The Campbell autobiography, released last June, is written in the modest style of True. Trimmer was the primary author in close collaboration some 20 years ago with Campbell. Charles Poling, a freelancer and novelist who also wrote the memoirs of the late Gov. Bruce King, was engaged to fill a gap in the narration.

The two introductory trips at the end of the Campbell administration 50 years ago told me a lot about two of his priorities – education and health care. In his two consecutive two-year terms (the limit then), 1963-66, Campbell had reformed financing of public schools and higher education and allocated bonding for new buildings. In health care, he modernized mental health treatment, earmarked county taxes to pay medical bills of the indigent, and with Senate leader Fabian Chavez created the UNM Medical School.

Campbell’s remarkable record in concert with an overwhelmingly Democrat legislature, also included creation of a State Personnel Board to thwart political patronage, creation of a constitutional revision commission, and judicial reform, also with the help of Chavez, including abolition of the corrupt justice of the peace system.

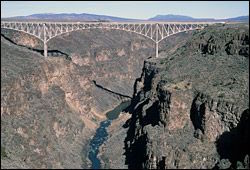

Rio Grande Gorge Bridge (blm)

But Campbell now is remembered, if at all, as a builder. The Rio Grande Gorge Bridge, location of a half dozen movies and subject of millions of tourist photos, is his. It was a campaign promise to the North, and he got it done by 1965 by using all state funds and avoiding federal highway funding delays. The state capitol, a political if not architectural masterpiece, was his project, along with an adjacent state library.

Designing a library into the new capitol complex struck me as a stroke of enlightenment. It was symbolic. It was consistent with Jack Campbell’s engaged philosophy of merging knowledge and science with governing.

But, let me ask, does anybody care? I mean, isn’t it really the personality of politicians that people now find interesting in this age of politics as entertainment? By coincidence, this book is a test – for, Trimmer and Campbell wrote the easy parts first, leaving the last three years of the administration for later. Then Campbell died, in June 1999 at age 82.

The manuscript – call it Gubernatorial Lite – rested with Maury until, as I understand it, former U. S. Sen. Jeff Bingaman retired in Santa Fe and took an interest in the story of his former law partner. Bingaman, Trimmer, Poling and Campbell’s son Michael, also a lawyer, interested UNM in publishing the book with Poling’s insert on the Campbell administration – 130 well-drafted pages in the middle of a 404-page book. Those chapters are in the third person and, of course, lack the personal commentary of Campbell and the polish of Trimmer.

In the autobiographical pages, Campbell’s war episodes are gripping and, yes, terrifying, but some are Catch 22-ish, like the account of trying to comfort the commander who became hysterical during an earth tremor. On the light side, his first-person recollections of being a gun-fumbling FBI special agent in Los Angeles and Washington would make a good pilot for a TV comedy. So would his story of entertaining poker-playing, Old Crow-drinking cowboy legislators as a lobbyist in Santa Fe. There’s a line about a legislator-historian who had “an unrequited love for higher office.”

Or take the tall politician whose official ballot name was Ingram B. Seven Foot Pickett. He was elected and reelected to the State Corporation Commission by astronomical margins, even though his opponents said he was only 6-foot, 10 ½ inches. (I once asked Trimmer what happened to Pickett. “Seven feet under,” he responded.)

So here’s a book that could not have been published without the insert, but you can skip it and still fully enjoy the book and its entertaining lessons. I mean, Campbell says in the introduction that most autobiographies are boring and, “I didn’t want to spend any of my limited time crafting such a tedious chronicle.” Though his life had been “exciting and generally happy,” he said, “I would like my story to tell more about an era than about one individual.”

And it does. Every page is illuminated by history – the depression, the war, the postwar U.S. economic boom, and the scientific enterprises so important to New Mexico. It begins with his two years in the Pacific war zone – Bougainville, Guam, Iwo Jima – when, as he says, “Weeks of intermittent terror were separated by months of comparative calm, though the war was always on our minds.” It was a time to make plans, in case he survived.

After the war he married Ruthanne DeBus, whom he met as a coworker during his 18 months with the FBI. They settled in Albuquerque and Roswell and began raising a family – Patricia, Michael, Kathleen, and Terry. He joined a law firm that represented energy producers and became executive secretary and lobbyist for the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association.

From Roswell, Campbell won a seat in the New Mexico House at age 37 in 1954. He backed John F. Kennedy early in the 1960 primaries while most of the New Mexico Democratic party was backing Lyndon Johnson. In the 1961 legislative session he was elected speaker of the House in a dramatic vote determined by one practically illegible paper ballot. After the 1962 session he began his campaign against Gov. Ed Mechem, a popular conservative Republican who was seeking reelection. “Limited government has its appeal, but sometimes inaction is intolerable,” Campbell says with reference to his campaign theme. He won with 53 percent of the vote.

“I suppose my decision to run for governor was a triumph of ambition over knowledge,” he says. “The title of ‘governor of New Mexico’ had been a somewhat dubious honor for more than 360 years.” Onate and Peralta were only the first to be disgraced. “I had been involved in politics long enough to realize New Mexicans had contradictory attitudes toward the office of governor. They wanted their governor to be a leader, but they were afraid to trust him with the power to govern.”

He closed his first legislative address as governor with these words (though they are not in the book): “Politically unpopular decisions may have to be made. Local considerations may have to give way to the sate-wide interest. Concern for reelection for all of us may have to yield to what we believe is right and best.”

Out of public office, Campbell continued as a matchmaker between government and science. He promoted his philosophy through interstate groups and returned to lawyering and lobbying in Santa Fe. He was elected to the board of St. John’s College, the unique Annapolis institution that created a twin campus in Santa Fe with his encouragement in 1964. St. John’s teaches the great books of western civilization. The Santa Fe campus in addition has a master’s program in the eastern classics (Disclosure: I am an MA graduate of this program.) The students do not compete for grades, but they must participate in seminars, write papers in every class and defend their writing in oral examinations. The faculty members do not flaunt their doctorates, preferring to be called “tutors.” The classes are seminars. The subjects are universal.

Universities, contrary to the name, or conglomerations of specialties. And perhaps this contrast affected Campbell’s relationship with the University of New Mexico, despite his friendship with Tom Popejoy, the venerable president of UNM. In 1969 the then ex-governor became director of UNM’s Institute for Research and Development, a government planning effort that he had helped create with funding from the War on Poverty. It became a ponderous agency of some 175 fulltime and part-time employees. And Campbell resigned in frustration. While this is just an item in the book and he is no complainer, his comments raise a fruitful issue. That is, he condemns “faculty members who resented an outsider getting involved in their game” and, “academicians entrenched in internal politics.”

You can see the shadow of Campbell’s UNM experience on the subsequent creation of the Santa Fe Institute, famed as the home of advanced math involving complexity and chaos theory. Campbell was the lawyer among the founders, and they agreed the advanced institute should not be affiliated with any university. The reasoning was that its goal of synthesizing physical and social sciences had to be free of specialists. Trying to free up academia, Campbell says, “has all the implications of trying to move a cemetery.” I am sure there are people at UNM who are aware of the problem. The book is a publication of the same university.

The UNM critique recalled what, I think, must have been another disappointment for Campbell, although he never expressed it publicly to my knowledge. His beautiful library, a resource for state employees as well as the general public in Santa Fe, was converted into more office space in the 1995 remodeling the capitol by the legislature, which owns the complex.

Campbell never again ran for office, returning to law practice and occasional lobbying. He was the most likely Democrat to succeed U.S. Sen. Clinton P. Anderson, who had announced he would not seek reelection in 1972. But in a fateful meeting at the tiny café in the Santa Fe airport terminal, young Albuquerque “mayor” Pete Domenici flew in and confided that he wanted to run for the Senate seat but would not do so if Campbell ran. The former governor said he would not run. So Domenici declared, won the seat, and served 36 years.

What about Trimmer? Maury went on to become director of public relations at St. John’s and then for the Oil and Gas Association. He and his wife, Ethel, are living actively in Santa Fe.

Campbell was a fisherman and throughout his career took refuge in his mountain cabin by the Pecos River. His ashes were scattered there.