Singing Through Ireland

A response to Churchill’s question

By Larry Joseph Calloway ©

We went to Ireland in the summer of the political year 2016 with a group that often burst out in song. They sang in enormous cathedrals, among grey monastic ruins, at a sacred lake shore, on a green moor above the ocean, and in pubs. Everyone was talking about Brexit and how it would screw the Irish – a familiar theme in the history of British politics.

In 1921 young Winston Churchill, a negotiator of the oppressive Anglo-Irish Treaty partitioning Ireland, rose in Parliament to defend it. He asked:

“Whence does this mysterious power of Ireland come? It is a small, poor, sparsely populated island, lapped about by British sea power on every side, without iron or coal. How is it that she sways our councils, shakes our parties, and infects us with great bitterness, convulses our passions, and deranges our action?”

Churchill did not answer his rhetorical question. I will not attempt an answer except to say that the symbol of Ireland is not a lion but a harp and that Ireland responds not with a roar but with songs and stories. Patricia and I listened to these as we accompanied the small Schola Cantorum choir of Santa Fe on a concert tour from Dublin to Sligo to Armagh to Westport to Galway.

There was, for example, a monk who had a white cat. In the tight margin of a scriptorium manuscript – vellum was precious in the ninth century — he scribbled a light poem equating his cat’s mousing with his own scribing. A translation from the Old Irish concludes:

“So in peace our task we ply

Pangur Ban, my cat, and I;

In our arts we find our bliss,

I have mine and he has his.

Practice every day has made

Pangur perfect in his trade;

I get wisdom day and night

Turning darkness into light.”

The curators of The Book of Kells at Trinity College in Dublin chose the unknown monk’s verse as an introduction to the present exhibit. For, in its sweet imagery the Book of Kells is about the monks who made it. They were graffiti tricksters. They stretched the vow of poverty to exclude possession of cats. Their surviving artistry is uniquely Irish, with bold calligraphy and bright colors. Their interlocking images are impressive in detail but not intimidating – even though the text of the Book of Kells is the four Gospels in Church Latin.

The early provenance of the national treasure is the history of the monks. They began it at an island monastery off the west coast of Scotland around 800 CE. They moved it to the monastery at Kells in 806 when Vikings in boats were slaughtering their brethren. They moved it to Dublin in the 1650’s when Cromwell was desecrating Catholic sanctuaries.

And the curators chose the last line of the Irish monk’s light verse as the headline of the exhibit: “Turning Darkness into Light.” This can have several implications. For one, the Book of Kells is the foremost example of what scholars call “an illuminated manuscript.” In another context, the Irish have always loved light: Easter fires on powerful summits, bright stained glass windows in ancient cathedrals, and the symbolic light in a window of the president’s residence.

And, the headline can mean a cultural light in the “Dark Ages” after the fall of Rome. “How the Irish Saved Civilization,” a bestseller by Thomas Cahill, made the case that when the light of Rome was extinguished by the waves of barbarian invaders, a dim light still shown on a far northern island.

We were lucky to spend more than an hour discussing this at the National Museum of Archeology with Dr. John Gillis, the lead restorer of a 1200-year-old book called the Faddan More Psalter. Archeology in Ireland specializes in bogs, the deep oxygen-free mud ponds where things don’t rot, and this book was found by a farmer in 2006 in a bag in a bog. It has been given its own display room next to the bog men – another Irish phenomenon in which the haunting beauty of, say, the hand of a dying man is not a sculpture.

We were lucky to spend more than an hour discussing this at the National Museum of Archeology with Dr. John Gillis, the lead restorer of a 1200-year-old book called the Faddan More Psalter. Archeology in Ireland specializes in bogs, the deep oxygen-free mud ponds where things don’t rot, and this book was found by a farmer in 2006 in a bag in a bog. It has been given its own display room next to the bog men – another Irish phenomenon in which the haunting beauty of, say, the hand of a dying man is not a sculpture.

Gillis and his team did not know what the drenched book was until he recognized a fragment’s line in Latin that translates “in the valley of weeping.” What they had was a common book of the 150 Psalms. The surprise, it turned out, was in the cover. Its soft leather was stiffened with sheets of parchment, a material made from reeds that do not grow in Ireland. They are from the Mediterranean. Therefore, there might have been a connection between Ireland and perhaps Egypt, Gillis surmised. It might have been a direct link, not by land through ravaged and deadly Europe but by sea.

There was another monk in another story. Seamus Heaney told it in a poem that begins, “And then there was St. Kevin and the blackbird.” The pious monk extends an upturned hand out the narrow window of his cell and the bird lands in his palm and settles down and lays some warm eggs. Kevin does not move for weeks until the young birds are hatched and fledged and flying. The ending of this poem written in the 1990’s would be relevant in a contemporary guide to Buddhist meditation:

There was another monk in another story. Seamus Heaney told it in a poem that begins, “And then there was St. Kevin and the blackbird.” The pious monk extends an upturned hand out the narrow window of his cell and the bird lands in his palm and settles down and lays some warm eggs. Kevin does not move for weeks until the young birds are hatched and fledged and flying. The ending of this poem written in the 1990’s would be relevant in a contemporary guide to Buddhist meditation:

“Alone and mirrored clear in love’s deep river,

‘To labour and not to seek reward,’ he prays,

A prayer his body makes entirely

For he has forgotten self, forgotten bird

And on the riverbank forgotten the river’s name.”

Our clean new high tech Volvo tour bus took us through mountains south of Dublin to Glendalough, a national monument. St. Kevin in about 525 AD founded a monastery in this mountain valley of two lakes. And then, though he was an influential noble in the world outside, he retired to a small cave by the upper lake. I imagined he lived out his life sitting in beauty and forgetfulness.

The 13 singers and director Billy Turney of Santa Fe were especially inspired among the monastic ruins in the rain, and as they sang a prayer of Mother Theresa for light, the sun burst through the clouds. Later they waded in the upper lake.

In his 1995 Nobel Prize lecture Heaney credited the poetic power of “the local” persisting beneath the “imposed ideological conformity” of nations. A companion theme was his confession that, “I began a few years ago to try to make space in my reckoning and imagining for the marvelous as well as for the murderous.” St. Kevin’s tale was both, if you accept the deconstruction that makes the saint a colonialist or a naturalist doing violence by interfering with the pristine and if you consider it was first told in the writing of a brutal Norman conqueror, he said.

And Heaney told a story out of Northern Ireland during “the Troubles,” which more directly illustrated the marvelous in the murderous. A minibus carrying men home after work was stopped by masked men with guns. They lined everybody up and ordered any Catholics among them to step forward. The workers were all Protestants, with one exception. The presumption was this man would be killed, but the others remained silent and one squeezed his hand in the dark as a signal they would not betray him. But he moved slightly forward and was jerked aside as the gunmen opened fire on the rest. They were not Ulster terrorists but IRA terrorists.

The walls against violence remain in Northern Ireland – thin as blades and high enough to bounce back a Molotov cocktail. Unlike strident anti-immigrant Americans, the Irish know about walls. And borders. The week before we landed in Dublin and walked easily through customs in the dazzling new international terminal, a majority in England and Wales, worked up about job-stealing immigrants and EU bureaucracy, determined the British decision to leave the European Union along with its principles of open borders and free trade.

Northern Ireland on the other hand voted against Brexit by 56 per cent. The independent four fifths of the island surely would have joined the minority if Ireland voted. But the north must follow the majority, like it or not, and a consequence would be a return of the 300-mile hard border across the island. Often we did not know which side we were on, unless a clerk asked to be paid in British pounds, not Euros. The bus driver and the tour guide, however, always knew. They remembered the militarized line erased by the Good Friday agreement in 1998 – the checkpoints with soldiers and officious inspectors. They knew the meaning of orange banners on certain North Ireland streets. It was nearing July 12, when Orangemen taunt Irish Catholics by marching to celebrate the victory of William of Orange over the Catholic James II at the battle of the Boyne in 1690. Yes, more than four centuries ago!

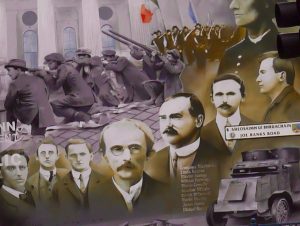

No one, it seemed, wants a hard border again, but few think the obvious defense against Brexit is realistic. Namely, unification – a unified nation separate from the United Kingdom. Not yet. There are too many evocative reminders. We were shown the antique miniature altars designed to be hidden from priest-hunters when Catholic practice was outlawed in the early 1800’s. We saw some of the more than 100 memorials of the 1840’s famine. We saw the posters with photos of the destruction in Dublin after the ill-planned, botched, but ultimately successful 1916 Easter Rising. We saw huge mural portraits of its doomed heroes.

And always there are the Irish movies widely screened and rented in the U.S.: “Michael Collins” and “The Wind That Shakes the Barley” (both about the civil war following the Rising), “Bloody Sunday” (about the massacre of peaceful demonstrators in Derry), “71” (about a wounded British soldier hiding among IRA terrorists in Belfast), “In The Name of the Father” (about the torture, false conviction and imprisonment of Irish scapegoats for IRA bombings), plus the “The Crying Game,” “Ryan’s Daughter” and “Odd Man Out.”

Unification actually would be re-unification. It was the Anglo-Irish treaty that split the nation geographically. Five violent years after the Rising, Churchill said in his speech that the treaty would “reconcile” Ireland just as Wales and Scotland had been reconciled. A century later there is not a lot of reconciliation. The centenary was hard to ignore.

At the famous (mentioned in “Ulysses”) Hodges Figgis bookstore on a table of new books about 1916 the title “16 Dead Men” stood out. It’s a story of the purported leaders of the Rising executed by the British. One was merely a poet. He married his sweetheart in jail the night before facing the firing squad. Our tour of Kilmainham Goal ended at the wall where 15 men were shot (one was hanged), day by day until an appalled uproar from the intimidated public stopped the executions. The Victorian jail had not been used for 30 years when local officials saw the value of restoring it to tell the Irish story and along the way sustain itself as a film set for hire. Half of “In the Name of the Father” starring Daniel Day Lewis was shot there.

The Brits shot the hell out of Dublin in 1916, blowing open the court house and the post office and other buildings taken over by the disorganized rebels, as shown in photos. At Marsh’s Library, founded in about 1700 by an archbishop, was a striking display of actual destruction: shot books. The soldiers and police in 1916 fired on the library, and heavy slugs ripped through the shelves of rare books. War does not much revere literacy.

George Bernard Shaw, the London playwright who grew up in Dublin, wrote, “I believe Ireland, as far as the Protestant gentry is concerned, to be the most irreligious country in the world.” How then can the protracted conflict be characterized as Protestant v. Catholic? The London playwright, speaking of his Irish childhood, added, “Irish Protestantism was not then a religion: it was a side in a political faction, a class prejudice . . . “

One day Pat and I and some others on the tour left the singers to their work with Michael McGlynn, director of the Irish National Choir. We took a side trip to Belfast, the metro center of Northern Ireland. The main tourist attraction there, unless you like walls, is the Titanic Experience at the Harland and Wolff shipyards. The elaborate media presentation celebrates the power of British industry and the skill of Belfast workers, most of them from the adjacent “Protestant” neighborhoods. They built the Titanic there. Launched from Belfast in 1912, the passenger ship was promoted proudly as the largest moving object ever created by mankind. But of course this is an Irish story. It sank.

The Titanic and its sister Olympic were an investment in the burgeoning immigration to the United States. On the maiden voyage it carried 706 passengers in third-class, 285 in second-class and 325 in first-class. News coverage of the tragedy focused on the rich and famous, as did James Cameron’s $200 million film (which cost more than the ship, in 1997 dollars). An old folk song kept running in my head:

“Oh they sailed from England and were not far from the shore

When the rich refused to associate with the pore.

So they put them down below, and they were first to go.

It was sad when the great ship went down.”

I suspect it’s an Irish song because that sort of sentiment raised suspicion of Marxist class warfare in America. But the song was true: the survival rate in first class was 62 per cent, in second 41 per cent, in third 25 per cent. Cameron, true to Hollywood ethics, had to clean up his third-class hero, making Leonardo de Caprio into a Picasso.

That night we stayed in the Northern Ireland town of Armagh in a spacious hotel next to a standard 40-foot wall around the police station. The destination was convenient for the concert at St. Joseph’s church in the small town of Carrickmacross south of the border in Ireland’s County Monaghan. The local church provided one of the best audiences of the tour, probably because the parishioners had been informed that the choir’s director was a descendant. Turney grew up in Santa Fe hearing stories about the community that were handed down by his maternal great grandmother who left and lived in America to the age of 103 without going back. Turney, a PhD environmental scientist at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory who also has a doctorate in sacred music from the Vatican, was the first in four generations to return to Carrickmacross. Near the end of the concert he disappeared. Suddenly the pipe organ erupted with Bach-like progressions. He was at the keyboard in the choir loft.

On the way to Sligo we passed through the hinterlands that inspired “the local” in the world-famous poetry of Yeats. We saw “where the wandering water gushes / From the hills above Glen Car,” and the Island of his homesick London poem that begins, “I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree.” Our guide recited Yeats’ “The Stolen Child” over the excellent sound system. He explained the poem refers to the Irish mythology of light woodsy creatures called faeries who trade ugly children for beautiful children. The refrain is:

“Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you

can understand.”

Yeats is architectural in the town of Sligo. The handsome poet in round glasses is painted large on at least two buildings along with quotations. A sign in a coffee shop says, “We speak Yeats.” It’s not likely that any tourist who has taken a required English course would respond, “Who’s Yeats?” He is now known so globally that two U.S. best-selling authors appropriated lines from his poems as book titles: Joan Didion’s “Slouching Toward Bethlehem” and Cormac McCarthy’s “No Country For Old Men.”

Heaney, in making his case for poetic locality and the duality, cited the 1923 Nobel lecture by Yeats, who he said “came to Sweden to tell the world that the local work of poets and dramatists had been as important to the transformation of his native place and times as the ambushes of guerrilla armies.” And, Heaney paralleled his own wish to accommodate the marvelous as well as the murderous with the admonition of Yeats “to hold in a single thought reality and justice.”

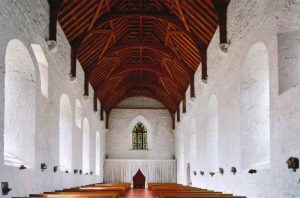

Next came Westport, a river town designed by a Georgian architect, with easy access to a heathery countryside full of weeping and faith. It is a Christian landscape overseen by Croagh Patrick the 2,500-foot pointed mountain where St. Patrick fasted for 40 days and nights and drove the snakes out of Ireland. People climb it year round as a testament of faith, and on the last Sunday of July hundreds summit, some barefoot. The traditional pilgrimage begins 20 miles from the foot of the mountain at Ballintubber Abbey, in a rural refuge near Westport. The abbey was celebrating 800 years of continuous worship. Its Romanesque church was founded in 1216, burned in 1265, burned again by Cromwell’s troops in 1563, and restored with contributions from around the world in the 1960’s. The poet C. Day-Lewis (father of Daniel Day Lewis) wrote of it as “The Abbey that Refused to Die.”

The Schola Cantorum sang here. The singers arrived several hours early for a photo and a rehearsal to attune to the acoustics of the high aisle-less nave under a timbered ceiling. I was told later that from the time they got off the bus until the reception after the concert none of them spoke. The simplicity and sanctity of this venue — the rough stone interior painted white, the deep window wells slanted to channel the natural light, the hewn doors heavy to the hand, the floating crucifix on invisible wires in midair at the transept – compelled my feeling that this was their best and most reverent performance.

Their program always opened with a single voice crying out “Miserere Miseris!” as the others joined her in a drone. The words mean “Have mercy on the suffering” and the medieval chant was in memory of the Black Death, Turney said. The plague of 1346-53 murdered a third of Europe including Ireland. The music of McGlynn’s arrangement rose up remarkably beautiful and resonant at Ballintubber Abbey. The chant had been discovered in the archives of Dublin’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and the Schola Cantorum performance earlier in that immense basilica brought it back.

The priest at the abbey invited everyone to tea in the parish hall. I approached him remarking that the five-feet-thick stone walls (unlike police walls) spoke of the church’s power and permanence.

“And beauty,” he added, significantly.

He was curious about New Mexico and had heard about the religious practices of the Penitent Brotherhood that evolved in centuries of isolation from the Church and its clergy. I compared Penitenties with the Scot-Irish Baptists and Methodists of the American South, whose religion evolved in New World isolation. They were Presbyterian immigrants from Ulster plantations intended to displace the Irish. In America they became known as hillbillies – a pejorative derived from the nickname of William of Orange: King Billy. (That is the story of my father’s people going back six generations in western North Carolina, and I’m sticking to it.)

The last night in Westport, we stopped in a pub near the hotel. A man with a white beard sat alone against a wall drinking a Guinness and playing a fiddle. The Schola Cantorum began gathering around him with the instruments in their luggage including a ukulele, guitar, tin whistles and Turney’s accordions. By midnight the place was packed and spilling Irish ballads into the street. Some French tourists at the door were yelling, “Hey, they’re singing here.”

The drive to Galway took us through lovely heartbreaking Connemara. At a grassy park we walked around a tall and twisted sculpture dedicated in 1997 by President Mary Robinson in remembrance of those who died in the famine of 1844-49. It is a ship of tortured souls. The thin stretched figures cling to the gunnels and the three bare masts. The Irish know it represents a “coffin ship,” named because so many refugees died on small boats in desperate passage for survival. One million died in the famine. More than one million escaped, most to America. My maternal great grandparents were among them.

I grew up accepting the cruelty of ethnic humor, laughing along with Irish jokes or hillbilly jokes because I did not identify with either ancestry. I lived in the U.S. West. I was an American! But one story stuck with me all these years for the mere inventiveness of it. How do you trap an Irishman? Well, you nail down a wooden crate and cut a hole in the top the size of a potato. Drop in a potato and wait for Paddy to come along.

“Sure and Begorrah!” he says, “It’s me dinner.” He reaches in, grabs the potato, and can’t pull out his hand because he won’t let go.

In Connemara we passed an eroded monument to the Doolough Tragedy, named for the lake nearby. The residents of a small village particularly hit by the potato blight were starving in the winter of 1849. Aid was available under British poor laws but they needed to be examined one by one. The two gentleman inspectors told the residents to report at 7 the next morning at Delphi Lodge, a hunting resort 12 miles away in the mountains. All night they walked. They arrived exhausted but on time, only to be told the gentlemen had gone hunting and would not return. In the long struggle home in a storm many – no one knew how many – died. The road was littered with bodies, according to one witness. On the monument, I learned, is a quote from Mahatma Gandhi: “How can men feel themselves honored by the humiliation of their fellow beings?”

I know. You’re wondering if the Irish are too invested in victimhood. As Yeats said in a poem he called Easter 1916, “Too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart.” Why go on vacation to see famine monuments? Why not ignore a million tragedies in another country at the same time America was accomplishing its Manifest Destiny? Why not walk away into the “waters and the wild?” Or should we face reality and avoid living in “fairyland?” (to use the American pejorative, which is almost another word). I remember the reality of an Irish family on the rocks at Achill Island where we all rested for a day. Schola Cantorum sang to them — “Danny Boy,” about a mother’s love for a dying son. It is almost a national anthem. The family was happy. The father’s withered leg made no difference.

Heaney, at his death in 2003 Ireland’s most celebrated poet and translator (Beowulf), sought synthesis and forgetting. Like Buddhist equanimity, maybe. So, back to the beginning story, cats catching and playing with terrified mice seem cruel. But the monk who cared for Pangur Ban knew he was just being what he was, a cat. What is regarded as the earliest poem in the Irish language equates a cat’s murderous work with a scribe’s marvelous work. Equanimity.

In this spirit – reality and justice in a single thought – the coffin-ship monument is placed so that from the best viewpoint you see Crough Patrick in the background. Our driver climbed the sacred mountain on our rest day in happy little Westport. (The idle singers burst out in song at a men’s clothing store owned by the brother of a Santa Fe immigrant friend of Turney. The editor of the local newspaper showed up and asked what was going on, then took photos.)

Galway is the fastest growing city in Ireland. Its pedestrian mall is full of international laughing not local weeping. We had a fine mean in a restaurant on the mall with a friend Pat had met in her travels, a scholar who was there to act in an Irish soap opera because she spoke Irish. She has a brother in America.

In a woolen store I noticed a black and white photo behind the cash register of two men posing in Irish tweed caps and tweed sport coats. The one on the right was the founder of the family business. The one on the left was John Wayne. “We made all his clothing during the movie,” the cashier said. The Duke was not always a cowboy. His frequent director, John Ford, did not always shoot in Monument Valley. “The Quiet Man,” filmed in Connemara and elsewhere in Ireland with John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara won an academy award for John Ford, who was Irish.

Eamon de Valera, the Irish politician who began his long career as an opponent of Churchill’s treaty, was born in New York City of a Spanish father and an Irish immigrant mother. The only mansion in Dublin’s Phoenix Park other than the president’s residence is the American embassy. The bonding of Ireland and America is unique. There are other Billy Turneys in the world.

In 1963 another Irish descendent “returned” as president of the United States. John F. Kennedy’s appearances in Ireland that June are still venerated with pictures hung in pubs or stores. In Eyre Square in the center of Galway I found a monument at the spot where Kennedy spoke briefly during his last stop in a successful European tour. He said he felt at home and concluded with the strangely ironical remark: “I must say that though other days might not seem so bright as we look toward the future, the brightest days will continue to be those in which we visited you here in Ireland.” Five months later he was assassinated.

Ireland has never regained the population of about 8 million it had before the famine. The common estimate of Irish descendants worldwide is 80 million, of whom 32 million are Americans. Mary Robinson placed a permanent light in a window of the presidential mansion in Dublin “to light the way home” for the Irish diaspora. I did not realize until I returned and started missing Ireland that the light was for me.

Larry: Your writing is a beacon for me. Rewarded as always. John