The Winning of the West and the Theft of Mt. Rushmore

How the Union army continued west after the Civil War. Reviews of "Lakota America" by Pekka Hamalainen and "West from Appomattox" by Heather Cox Richardson

How the Union army continued west after the Civil War. Reviews of “Lakota America” by Pekka Hamalainen and “West from Appomattox” by Heather Cox Richardson—————————————————

The Dec. 5 (2020) New Yorker has drawn attention to Pekka Hamalainen, the Danish scholar of American Indian policy. Here is my review of his first book, “Lakota America.”

Along T-shirt row in Deadwood, the gold-gulch town in South Dakota’s Black Hills, you can read silk-screened homages to bikers, gunfighters, gamblers, anti-immigrant soldiers (“If you are reading this in English, thank the U.S. military.”) and the armed protection of private property. The town’s history of lawless violence was the basic entertainment value of “Deadwood,” the HBO series a few years ago.

And Donald Trump is in the shops. He is dressed in black leather, armed and tattooed, with huge hands in control of a Harley motorcycle. In one scene his bitch played by Hillary is flying off the back seat. You don’t want to mess with this macho man.

The only relief from the bike-gun culture was a shop wall of real iron horseshoes made pretty with beads and silver Indian feathers — $40 each with the proceeds going to a refuge for abandoned horses. Yes! Let us remember the beautiful Western horse symbolizing freedom and the power to keep it. Equus created a new and prosperous nomadic culture in the New World. The horse let the Woodlands Indians of the east evolve into the Plains Indians of the west, as they migrated just ahead of the advancing Euro Americans. So writes Oxford historian Pekka Hamalainen in “Lakota America,” a new and thorough history of the fiercest group of the Sioux people.

The only relief from the bike-gun culture was a shop wall of real iron horseshoes made pretty with beads and silver Indian feathers — $40 each with the proceeds going to a refuge for abandoned horses. Yes! Let us remember the beautiful Western horse symbolizing freedom and the power to keep it. Equus created a new and prosperous nomadic culture in the New World. The horse let the Woodlands Indians of the east evolve into the Plains Indians of the west, as they migrated just ahead of the advancing Euro Americans. So writes Oxford historian Pekka Hamalainen in “Lakota America,” a new and thorough history of the fiercest group of the Sioux people.

He fleshes out the story that horses came to North America through Santa Fe. During the Southwest Pueblo (Indian) revolt in 1680 the conquistadores left many of their horses behind as they fled back to Mexico. The settled Pueblo people rid themselves of everything Spanish, and the surrounding nomads took the horses, he says. Replacing dogs as beasts of burden, horses enabled the Lakotas to expand their portable tipis and increase their possessions, dragged from camp to camp travois style as they followed the bison (buffalo). With the acquisition of firearms the Lakotas became dominant hunters and warriors against other Native groups. First came muskets from the French, then repeating cartridge rifles from the Canadians and Americans.

The horse-gun tradition is still celebrated in tourist towns across the central plains. Cody, Wyoming, has an unequalled firearms museum and a daily rodeo. The 2015 film “Songs My Brothers Taught Me” which has the ring of authenticity opens with the protagonist riding bareback on a half-broke horse and ends with his little sister visiting a rodeo. The middle scenes depict other remnants of a once healthy living culture. Writer-director Chloe Zhao is not Native American, but her innovative production was shot on the Pine Ridge Reservation with an improvising Lakota cast.

Hamalainen’s scholarly history presents a full picture of the Lakota fight against deracination (a word meaning uprooted that sounds more appropriate for the Lakotas whose roots were free floating). In that struggle Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and even Red Cloud were the most famous leaders — skillful as battle strategists, but also as publicists and negotiators.

War and diplomacy flourished in the Lakota campaign to save the wild Black Hills of Dakota Territory and the Wyoming grasslands further west. The pine-dark mountains were rich in gold, which the minimalist Lakotas had no practical use for and tried to keep secret. It was discovered in several places in 1874 and the big strike was in the Deadwood gulch in 1876. The Americans flooded in, and the First Nation warriors harassed them. Hamalainen refers to them by a Lakota name, wasiku.

It was a losing battle. The new people had superior armament, steel tools and steam power and seemed to be protected from deadly alien diseases like smallpox and cholera. The Lakotas and other groups withdrew from the Missouri, a wide river navigated by steamboats, but they could not escape the railroads. Two transcontinental lines bracketing the northern plains were approved by Congress with accompanying land grants as the Civil War ended. The Union Pacific on the south was completed by 1869, but the Northern Pacific was stalled by Lakota hostilities as its surveyors approached the Black Hills.

Hamalainen found an 1872 report in which the U.S. commissioner of Indian affairs wrote: “The Northern Pacific Railroad will of itself completely solve the Great Sioux problem and leave the 90,000 Indians ranging between the two transcontinental lines as incapable of resisting the government as are the Indians of New York and Massachusetts.”

He was wrong. The Lakota leaders were not going to be subjugated that easily. And their creativity was disarming. An example was a surprise confrontation with U.S. troops guarding railroad survey crews in the Yellowstone river valley. First the Lakotas fired on the army camp from a ridge. Then, in Hamalainen’s version of the story, “Crazy Horse, dressed in white buckskin and his face painted white, charged at a dead run across the picket line, taunting the wasicus. Sitting Bull walked toward the camp, sat down within firing range, and lit his pipe. Four warriors joined him. Ignoring the bullets whining by, he passed the pipe around, then carefully cleaned it, walked back up the ridge, and announced the fight over.” (This incident, which also is narrated in the Ken Burns production “The West,” is not footnoted.)

Red Cloud was more cooperative and diplomatic, but his rhetoric about reporting to agencies in the settled Missouri valley was not submissive. He told a conference of agents, “Look at me! I am not a dog. I am a man. This is my ground, and I am sitting on it.” And in one of his visits to Washington, he harangued President Ulysses S. Grant, according to a New York Times report, saying, “I have said three times that I would not go to the Missouri, and now I say it for the fourth time.” Grant abruptly ended the meeting, and Red Cloud would not participate in the traditional group photo.

The subtitle of “Lakota America” is this: “A new history of indigenous power.” It also is a radical history if you view it in the context of the Frontier Thesis, a founding document in the story of American exceptionalism. Frederick Jackson Turner, a young Wisconsin historian, announced it in a meeting of historians at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition. The essence of the paper is that the experience of the open frontier receding westward for four centuries, and settlement by free and independent migrants, defined American character. It ignored the fact that the frontier was already populated.

My reading of Hamalainen is that he implicitly proposes an oppositional military-industrial thesis: that the winning of the frontier was the military continuation of the war in the South. The North did not rest after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Gen. Grant at Appomattox in early April, 1865. The West was to be won in the same way the Civil War was won: by force. Only the propaganda, carried by the explosive growth of mass-circulation newspapers, was new. It replaced the southern rebels with the western savages. Hamalainen says, “The U.S. was gearing up to crush the Lakotas as a sovereign nation, and the president and the American people needed a different kind of Lakotas: primitive, treacherous, weak and controllable.”

Four years after Appomattox, Grant was president — commander of what Hamalainen calls “a Yankee Leviathan capable of inflicting enormous harm to crush any rebellion, whether domestic or foreign.” The nation, now formally undivided, was “changing at its very core into an imperial nation-state obsessed with land and authority and intolerant of alien ethnicities and competing sovereignties within its expanding borders.”

Industrialization of news — by the steam-driven rotary press, the telegraph news services, and distribution of mass newspapers by railroad — was the beginning of the national mainstream media. And so the media, in Hamalainen’s view, were completely supportive of the Indian wars, and the Lakotas were universally conflated with, in his words, “rebellious blacks, Chinese immigrants, disaffected farmers and labor activists as an acute threat to the fragile industrial order.”

The Union military was not confined to action in the South during the war. The goal of the Confederacy was to extend its slave-holding nation to California, but it could not maintain two fronts. The Union blocked the Confederates in New Mexico, and one decisive battle was at Glorieta pass east of Santa Fe.

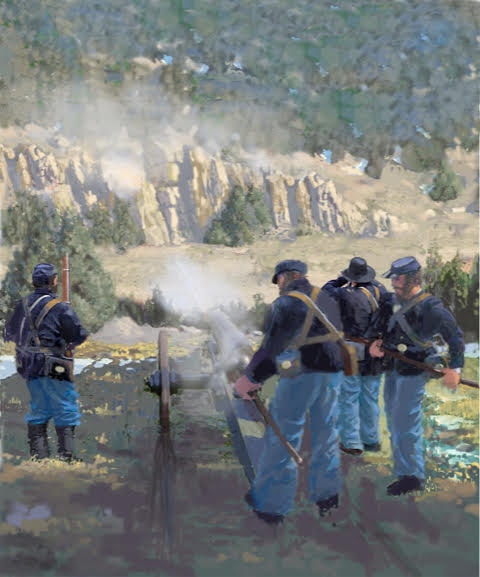

The U.S. Cavalry troops in the west wore uniforms — with light blue trousers and dark blue jackets and hats — indistinguishable at a distance from the Union troops in the Civil War. The western historian-novelist Wallace Stegner remarked that the reason the Canadian Royal Mounted Police wore red uniforms was so they would never be mistaken for their U.S. counterparts.

President Grant in 1876 sent 7,000 Cavalry troops to the western plains under the command of Gen. George Armstrong Custer. The pattern of dawn military raids on Indian encampments by soldiers who recognized no tactical difference between hostile warriors and women, children and old men was exemplified as early as 1864 by the massacre at Sand Creek in southeast Colorado. At least 150 were killed by armed volunteers under the flag of the Colorado militia.

Custer, a general since Gettysburg, knew the pattern. His first dawn raid was on an encampment of a non-combatant named Black Kettle. Custer tried it again at the Little Big Horn river, a tributary of the Big Horn, which in turn pours into the Missouri. But what Custer that morning assumed to be a small encampment embodied thousands of ready Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapahoe warriors.

So in early July 1776 as Americans celebrated the centennial of Independence, the shocking news everywhere was about the disaster on the Little Big Horn. About 260 soldiers of the Seventh U.S. Cavalry lay dead in the meadows along the river. The ridge crest where Custer made his “last stand” was dedicated three years later by an enraged government as The Custer Battlefield National Monument. In 1991 it was renamed Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument and the site was corrected with additional monuments to Native American warriors — Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapahoe and even the Crow who were scouts for the Seventh Cavalry.

On that grassy hill in southern Montana now an wirey steel sculpture of horsemen in battle stands above the weathered stones where each dead soldier was found. The new tribal monuments bear mass epitaphs with praise for deaths in the fight “to save our land and culture.” It is ironic that everywhere at the national monument you can hear Interstate 90 and trains on the tracks of the former Northern Pacific that parallel the highway. The scream of technology disturbs the dead.

Another ironic parallel of new technology with the first culture of the plains is on a crest in the mountains between the Big Horn and Little Big Horn. There are two high points at 10,000 feet altitude. On one is Medicine Wheel National Historical Monument, a flat circle 80 feet in diameter with 28 erratic spokes that seem to be sight lines. On the other is a white sphere said to contain instruments for the control of air traffic in a circle involving three states.

The rail fence protecting the medicine wheel — more appropriately called a hoop since the stones were placed centuries ago by people who did not have wheels — is sanctified with small offerings. Returning down the mile-long trail Patricia and I saw a Native family walking up. The literature for the place says similar circles 800 to 3,000 years old are everywhere in the West. They are not as well known as covered wagons, six-shooters and cowboys.

The old U.S. Indian-head nickel with bison on its obverse side is another ironic memorial to the wild plains that were transformed by the advance of industry. Professional “hunters” in the end were killing 3,000 bison a day, Hamalainen says. And this slaughter was part of Buffalo Bill’s famous Wild West show.

Mainstream ignorance of centuries of indigenous culture aside, there is no reason to assume Native Americans would immediately forgive and forget massacres like Sand Creek. Hamalainen sees a motivation for the unrestrained violence at the Little Big Horn in the fact that survivors who were able to escape Sand Creek had been taken in by the Lakotas. Twelve years was not too long to wait for retribution. On the other side, Wounded Knee, where more than 250 Lakota men, women children were surrounded and mowed down by artillery from a hill, was 14 years after Little Big Horn.

A striking story of artful retribution in that violent era is repeated in Hamalainen’s book. An Indian agent who denied rations to Lakotas when they could not pay said, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.” He was killed in a local uprising, and his body was found with mouth stuffed with grass. The story is remembered by Layli Long Soldier, a Lakota poet, who speaks of it in the first poem of her book “Whereas:”

Now

make room in the mouth

for grassesgrassesgrasses

Heather Cox Richardson, a Boston College historian of Reconstruction, says, “The nation’s strongest cultural images of the postwar years came from the West.” A theme expressed by her book “West From Appomattox” is that in the 35 years following the end of the Civil War a middle class was in process of becoming the political majority. The politics solidified when Teddy Roosevelt — “that damned cowboy,” as an Eastern oligarch put it — became president at the dawn of the new, “American,” century.

Richardson recalls a map circulated on the Internet after the 2004 election. The red and blue were states were superimposed on an 1860’s map. The red matched the southern states that supported the Confederacy plus the U.S. territories of the western plains, the blue matched the states that supported the Union.

Her interpretation of this duplication has to do with opposed philosophies of government rather than simple racism. (Blue states favor social programs. Red states favor limited government, etc.)

During the Civil War, the Republican Congress had imposed national taxes for the first time, raised a million-man army, increased government bureaucracy, and created the 13th amendment outlawing slavery with the grant of power to enforce it. Richardson notes this was the only direct establishment of authority in the constitution, which otherwise limits federal government.

In her view Republican Northerners accepted African Americans who exemplified the ethic of hard work and individual responsibility, as distinguished from those who supposedly waited for government handouts and joined protest groups. When labor strikes raged in the rapidly developing industrial North and fears of revolution were induced by dispatches via the new Atlantic cable about the Paris Commune in Europe, the Republicans abandoned the cause of the freed slaves. The Jim Crow era began, unopposed by the North.

The media characterization of the eight years of black-majority South Carolina government as corrupt, inefficient and even communistic eventually destroyed it. Richardson observes that one of many misperceptions was that that legislature’s majority was made up of former field hands when actually they were “prosperous professionals.” The Obama administration memoirist Ta-Nehisi Coates, with subtle reference to the Trump era, says white racism required that the South Carolina experiment be seen as a failure. Racism is prior to truth.

In the West, as Hamalainen narrates, Native Americans were expected to settle down on Indian land and learn to work, mostly as farmers. (Nice plan for believers in the Protestant Ethic, but it was subverted as always by practical politicians. Congress enabled allotments of reservation land to individual Indians, resulting in resale to non-Indians. The allotment scam was not repealed for 30 years.)

Another tragedy of good intentions was the creation of boarding schools by Christians who called themselves “Friends of the Indian,” as portrayed in the Ken Burns series. When Trump began imprisoning the children of asylum-seeking migrants, a Tewa woman told me the elders of her Pueblo were saddened because it revived their memories of being forcibly taken and schooled when they were young.

A contrasting and subtle scene in “Songs My Brothers Taught Me” shows a high school class at Pine Ridge. The bearded Anglo teacher is asking the boys what they want to be. Except for one who is asleep at his desk due to a hangover, they all say they want to be rodeo bull riders or bronc riders. Nothing is said about the bull snake coiled around the arm of one boy or the tarantula teased by a girl, or the ugly beetle crawling on a desk, or the cute rodent of some kind on the teacher’s shoulder.

The cultural subjugation is expressed at Mount Rushmore, where in 1927 work began carving the heads of four U.S. presidentsinto what Hamalainen calls “the granite of the Six Grandfathers, a spiritually vital part of the Black Hills that many Lakotas believed had been taken from them illegally.” Originally the plans also called for depictions of Lakota leaders, but like the Treaty of Laramie that seemed to grant access to all the grasslands where buffalo were hunted, this was a false promise. In 1948 a non-profit group of non-Indians sponsored a Crazy Horse monument in another granite face. The blasters are still at work, and the project is beginning to attract tourists at $20 a head.

As the industrialization of the plains progressed, dams in the Missouri watershed absorbed 550 square miles of Indian land. Yellowtail Dam on the Big Horn is named for a Crow leader who favored it. The surrounding national recreation area has wild horses. When a highway was being built into the mustang reserve several years ago, a paving foreman told me, the crew never saw a horse but each morning they found horseshit piles carefully dropped where they had finished work the day before. We camped near the Yellowtail reservoir and took a boat ride in the spectacular canyon full of big horn sheep. There was a sign on a cliff that said, “Entering Montana” going downstream and “Entering Wyoming” returning.

From our RV door the grassland continued to the horizon, free of all human construction, a reminder of what the American plains once were. We rolled on across Wyoming and camped at Devils Tower, a sacred-looking natural monument 700 feet high now crawling with roped climbers. We walked around it in the morning.

Then we arrived in historic Deadwood with its biker culture, and I wondered if Harleys are the new horses, iron horses, riding like the cavalry and the Indians. . . on motorcycles. Naww. Ordinary white motorcycle clubs, despite Republican efforts to create Bikers for Trump, avoid government. And the number of Native American motorcycle clubs seems unrecognized — except for RedRum MC with the logo “Warriors 4 the People.” This group was on national TV riding in support of the encamped (and surrounded) protestors against the Dakota Access pipeline, which would run within a quarter mile of the Sioux Nation reserve and threaten its water supply.

Trump is a white biker only in the dreams of people who draw him for T-shirts, and they would never dream of drawing him as a Native American biker. But there is no doubt which side he would be on, if he qualified as a biker and if white bikers actually were as racist as he is. As soon as he could, three days after being sworn in, Trump rescinded the Obama administration’s halt of the Dakota Access pipeline.

Again, industrialization overwhelms traditional land and culture. Still, as always, there is hope. In the movie, “Songs My Brothers Taught Me,” we see the ravages of alcohol and drugs and gang violence, an absent mother who has had too many men in her life, and father with about 25 children from nine women — all through the eyes of a 12-year-old girl whose only reliable family is her big brother.

At work sorting things for sale by an artist, the girl asks him why so many T-shirts and other items incorporate the number seven. The number is sacred in the bible (God rested on the seventh day, etc.), he says. “Seven is our culture’s most sacred and revered numbers. Crazy Horse said, Everything seemed to have ended at Wounded Knee, but it will all begin again in seven generations. And that’s you.”

It’s a beautiful ending.

thanks for interesting read about the military and the ‘settling of the west’ Another friend had just recommended Heather Cox—-I like it when friends coincide. Nice to see the paintings by your old friend; the Sand Creek painting is particularly nice. During your next visit to Montana you should stop by the Big Hole massacre site. Ghostly tipis in the dawn light will make you cry. .

Good article and insights. Glad you mentioned the film ‘Songs My Brothers Taught Me’. The filmmaker Chloe Zhao made another film titled ‘The Rider’, which too casts locals in most of the roles, deals with rodeos and was shot in the same region of the country. An area that most of Hollywood tends to either ignore or view in pejorative ways. The only way to understand the people is to also understand the history, which of course gets glossed over to make it easier to digest.

Thanks, Matt. I watched three late 1950’s Westerns starring Randolph Scott the last three nights — same director, same writer, same location. Almost same plot — half dozen good and bad guys with guns on the trail, one woman with bad or dead husband. What caught me was the extraordinary horses and horsemanship. There must have been an advanced wrangler industry in Hollywood then. I doubt that resource exists anymore.