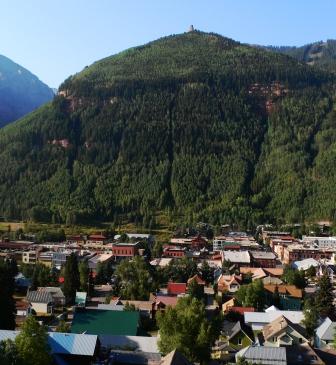

Report From The Telluride Film Festival

By LARRY CALLOWAY

Copyright 2010

A RELUCTANT prince is catapulted to the throne in a perilous time. Desperate to overcome a disabling speech impediment, he falls under the influence of a wily commoner who is distrusted by all advisors including the archbishop. Will the new monarch rise to the challenge of history?

“The King’s Speech,” which received its very first screenings at the Telluride Film Festival, is, well. . . Shakespearean. Except, it is a modern history and totally accessible. It’s the story of George VI, who as a young prince was practically struck dumb in public because of his painful stammer. Director Tom Hooper and actors Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush, who attended two screenings, received standing ovations. Screenplay writer David Seidler, drawn to the story of George VI because he too stammered as a youth, deserves to share in the applause (and in the future awards already being suggested by critics even though the film will not be released until late November).

Firth plays a proverbial second son, namely Prince Albert whose arrogant older brother succeeded George V only to abdicate in December 1936 to marry a commoner, American Wallis Simpson (toward whom the script is not favorable). Rush plays Lionel Logue, an Australian whose unconventional therapy came from years of treatment of shell-shocked World War I veterans. The primary plot is the unlikely relationship between this uncertified speech therapist and the prince who concedes he has never talked to a commoner. The relationship gets off to an apparently bad start when Logue calls his client “Bertie” and asks, “Do you know any jokes?”

That and some of the other “best lines” were actually spoken in the consulting room in 1939, Hooper said. How did he know? A few weeks before shooting began, a grandson of Logue found his unpublished diaries in an attic and made them available. Rush said the diaries were invaluable in the effort to “create an Aussie who didn’t fall into international cliches.”

The main historical context is, of course, the rise of Hitler and the British declaration of war against Nazi Germany. In both the writing and the directing the film dramatizes fascinating details of the period, including the importance of the new mass medium of radio. Hooper’s direction creates a BBC presence through ingenious establishing shots, emphasizing its direct broadcasting to some 50 colonies and possessions around the world. The British Empire was still enormous, and the king was also “emperor.”

Seidler must have done some very patient research. Patient, because he proposed the story idea in 1980, asking Buckingham Palace for permission from the queen mother, who said, according to Hooper, “Yes, but not in my lifetime.” She died in 2002 at 101. In the film she is played with noble yet entirely human charm by Helen Bonham Carter. Hooper (director of the positive HBO miniseries “John Adams”) said the royal household has been kept informed as the movie developed.

Hooper said his own background as the son of an Aussie mother and a father who was the product of British boarding schools contributed to his direction both of Firth as the second son of the overpowering George V and of Logue, the snubbed Aussie. The psychology is something anyone raised in a family and anyone who has been an outsider in a privileged society can relate to. This movie will entertain as a psychological thriller and inform as a history of a period that is passing from living memory. And, I suppose, it will endear the royal family to almost everyone, as did “The Queen.” (Elizabeth is a sweet little princess in this new film.)

Firth, fascinated by the mysterious force of stammering, told a Telluride audience that he began to stutter off camera during the filming. He developed a headache and his left arm became numb. “I did not know what parts were tensing up.” He called Logue’s revolutionary approach “psychotherapy by stealth.” As a field of study, stammering is of great import. “The voice is the ultimate expression of who you are,” he said.

FILMS that express voice, poetic voice, have been my favorites over the years, 18 years, at Telluride, which loves this genre that is not generally available or profitable. Korean director Lee Chang-dong’s “Secret Sunshine,” acclaimed three years ago at Telluride and winner of an award at Cannes, is still not available for rent in the U.S., where it was shown only a few times, if at all.

This year Lee returned with “Poetry,” about Mija, an aging widow with incipient Alzheimer’s who, ironically, signs up for a poetry-writing class. The instructor is an authoritative academic man. He holds up a lovely red apple, demonstrating his superior sensibility. Mija, striving to emulate him, is discouraged. She does not see. On a walk in an orchard all she can come up with is: “The apricot throws itself to the ground / To be trampled and crushed / In preparation for its next life.” The lines signify the story running in the background, so to speak, about the suicide of a farm girl who has been gang raped by urban boys in her school.

“Most of us consider poetry as writing about what is beautiful,” Lee said through his translator. “Mija is looking at nature and asking, What is beauty? However, poetry is not just about what we can see, but about what can’t be seen with the eyes.” As the fathers of the rapists put up money to pacify the single mother of the dead girl, Mija (with good reason) searches for the bereft woman in the countryside where she tills a small farm plot.

“Then shall two be in the field; the one shall be taken and the other left. / Two women shall be grinding at the mill, the one shall be taken, the other left,” says the narrative voice, her voice, reciting from the Gospel of Matthew. (As in “Secret Sunshine,” also about a woman grieving the death of a child, Lee incorporates Christianity in his subtle critique of Korean society, artfully presenting the consolations of the foreign religion as empty.)

“We have sadness in our lives, darkness in our lives,” Lee told a Telluride audience. “Mija has found beauty in the darkness and the pain.”

In a more accessible genre, “Precious Life,” by Israeli director Ehud Bleiberg (“The Band’s Visit,” 2007) is an evocative documentary, shot in video as it happened. Telluride streets buzzed with talk about the story – a heroic attempt to save the life of a baby from Gaza during the Gaza War 18 months ago. Broadcast journalist Shlomi Eldar, an Arabic speaker, promoted it on the news when the five-month-old “bubble baby” was brought to a hospital in southern Israel.

All that could save the infant, named Muhammad, was a bone marrow transplant, but the wary and intimidated parents had no money. An anonymous Jewish donor gave the necessary $45,000 in memory of his son, who was killed by Palestinians. Muhammad is saved, but that is not the end of the story. The journalist was astonished when the mother told him, on camera, that she would be proud if her son grew up to be a “shahid,” literally “witness” or martyr, which is to say, a suicide bomber. She wouldl not back down, even when asked, “Don’t you believe Muhammad’s life is precious?” No, she said, “We are not afraid to die.” When a Jew dies, Israel goes crazy and kills hundreds of Palestinians, she said.

And this in a way is true. In response to Hamas rockets, Israel launched a devastating air and ground attack on Gaza, where 1.2 million people live confined in less than 140 square miles. A Palestinian doctor allowed to practice in the Israeli hospital called the journalist on the air, crying in grief because his house was hit by an Israeli shell and his three daughters lie dead. He asks on camera later: How can you care so much for the life of one baby for months and months and then kill hundreds in a few seconds?

THE WORLD comes to Telluride in films, carrying such questions as that. And because it is an annual celebration of movies in themselves, without political motives or fundamental themes, most go unanswered. The point is to ask them.

Mark Cousins, an eloquent young video essayist from Edinburg, was invited to Telluride to show his poetic “The First Movie,” which asks the question: Can imagination overcome the terror of war? Cousins grew up in Belfast in a time of unrestrained sectarian violence – bombings and shootings were part of everyday life. He found refuge by going to the movies, where he felt safe in a world of imagination. “Movies were the not-war,” he told a Telluride audience.

Cousins came up with the idea of making this refuge available to children in Iraq. He found a Kurdish village so deep in the mountains that its children had never seen a movie. Setting up a projector and screen, he showed them “E.T.,” among others. Then he handed out digital cameras.

The kids came back with a reality that surprised him. Among the sequences were constant references to something he had never suggested himself, “the chemical rain” in which hundreds had died two decades earlier. (Can anybody disagree with the execution of Saddam Hussein?)

But they came back with beauty, too. One named Muhammad had two and a half minutes of a younger boy playing with mud at the edge of an irrigation ditch. Muhammad screened it with a commentary about what the boy was imagining as he played. “He had filmed a child’s thoughts,” says Cousins in his narrative. Muhammad reminded him of his eight-year-old self in war-torn Belfast except, “He had made his first movie!”

Later I had a conversation with Cousins in which he mentioned some of the problems that were deliberately not dramatized in his film – the $15,000 cost for just getting to and from the remote village, the hiring of security guards (the American military was nowhere to be seen), the threat from the secret police, the poisonous scorpions in his room at night, the relentless sun. He said, and I took it as an explanation: “I did not want to do journalism.”

I told him I was a former journalist. He apologized, noting that he writes a monthly column for a newspaper at home. I said an apology was unnecessary, since I viewed my retirement as an escape. He was amused to meet, in his words, “a recovering journalist.” Later, it occurred to me that the journalistic approach to this village would have to establish, first, that it was one of thousands subjected to genocidal attack with weapons of mass destruction. How, then, could a practicing journalist follow this with shots of children laughing and playing and chasing balloons, joyfully being children, as do the first shots in Cousins’ film?

We talked of a long stationary shot near the end. Cousins had seen a girl in a purple dress herding goats to pasture every morning. Early one morning he set up his camera on a hill and filmed her following the goats up a deserted dirt road below. But she stopped suddenly and went off the track to pick a pomegranate, then ran to catch up with the animals. There was an indefinable beauty in the shot, perhaps enhanced by Cousins’ narrative in which he says, in so many words: “I wondered how long in her life she would be able to have this quietude, and would this be a memorable moment in her life?” The answer for her would be, of course, No. But for us. . . Yes. Cousins told me that he had a notepad beside the camera and as it recorded he spontaneously wrote the narrative. To me this was a definition of poetic voice in the digital age.

There were other “not-war” films at Telluride this year, all from the middle east or central Asia. “Of Gods and Men” is a true story, well told, about the half dozen monks of a French Catholic monastery in north Africa during the Algerian civil war. Although they serve the local Muslim community, operating a medical clinic among other things, and although they are loved by the local people, they are in grave danger from a local war lord and must decide whether to flee. The outcome is visually stunning.

“Carlos,” by French director Olivier Assayas (“Summer Hours”), is the inconclusive story of the international terrorist Carlos the Jackal. Assayas justified the 5 ½ hours of screen time (the result of only 91 days of shooting) as necessary in order to present all the facts. I found it repetitive, but there is a new market for episodic movies on the small screen.

“Border” follows a pregnant water buffalo from bombing to bombing in Armenia, isolated by closed borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan. The folks in the film are almost wordless. No voice.

“Incendies,” which translates as “scorched” is a genealogical mystery by French Canadian Denis Villeneuve, set during the Lebanese civil war, which involved Christians and Palestinian refugees. The violence is painful to watch, but the complex plot of this story, originally a stage play, distracted me from the imagery. The plot pays off. All is explained. Still, I walked out thinking that some movies make better books.

THIS VERY issue came up in a public conversation between two great contemporary authors, Kusuo Ishiguro (“Remains of the Day”) and Michael Onaatje (“The English Patient”). Ishiguro said the faithfulness of a movie to a book is no longer an issue. Concern about it was “a generational thing.” Screenplays are translations, and some things don’t translate, he said. A story is like a song. You write it and the singers make it their own. “You put the material out there, and the actors make it better,” he said, noting that the writer is one but the actors are many. While Ishiguro likes collaboration, Onaatje said he prefers his solitude as a writer.

Ishiguro’s “Never Let Me Go,” translated, so to speak, by British director Mark Romanek, is a dreary story about children created and grown in order to provide donor organs. Despite the believable performances of Carey Mulligan (“An Education”) and others, I could not suspend disbelief. It would have been better as a full science fiction movie.

“Tamara Drewe,” also set in the English countryside, was a happy antidote. Directed by Stephen Frears (“The Queen”) it has sexuality (Gemma Arterton), wit (although some bright lines were lost to me in the British idiom) and literary references (Thomas Hardy lived in the country and loved young women like Tamara). The story comes from a graphic novel, which I suppose is the new “book.”

TELLURIDE likes ethno-films, and one of the world’s first, “Moana,” shot in Samoa in 1923-24, had a rare screening before a full house. Robert Flaherty (“Nanook of the North”) took his wife and three daughters to the South Seas with him during the two years of filming. His youngest daughter, Monica, in her later years became obsessed with creating a meaningful soundtrack for the 16-milimeter black and white film. She returned to Samoa, found some of the original cast, and recorded songs and sounds. She died in 2000, and the current version was finished by Flaherty’s great-grandson.

If Lavina Currier (“Passion in the Desert,” 1997) made a movie out of the Flaherty family story, which I found more interesting than the family film, it would come out looking like her “Oka! Amerikee.” This surrealistic film was inspired by the journals of musicologist Louis Sarno, who recorded pygmies in the Central African Republic. It’s a dreamlike film that at times seems to satirize itself, and because the scenes are set up and acted, it likely has no more anthropological value than “Moana,” also intended to make money as a feature film.

“Mother Dao, The Turtlelike,” is a 1995 production consisting of silent footage from archives in the Netherlands. Shot between 1912 and 1933, these documentary films were intended to promote Dutch colonialism in Indonesia. The postmodern editing and the soundtrack of native poetry and music turns the Dutch p.r. on its head. Onaatje, this year’s Telluride guest director, chose it as one of his six presentations. In his notes he quotes Susan Sontag, who said, “Mother Dao has to be the strongest, most important film ever made in a fascinating genre.”

The visual sequences of workers in steam-powered factories that process the resources of their former homelands are themselves devastating. Over and against the hundreds of dark, bare natives are the Dutch masters, dressed all in white. I used to think white was the color of the dress of Europeans in the tropics because it reflected heat. Now I know: it was a uniform.

The combination of the voiceless images of people now gone with the spare words of the soundtrack – unattributed native poetry – can bring tears to your eyes. I dashed down a few lines, some inaccurately, from the subtitles in the dark:

“Crows are so fearsome / And hunger is a crow.”

“I am the fish from the primal sea / Gasping on the shore for water.”

“God almighty, Lord full of pity / I hope you will protect me. / It is useless to resist the wrath of time.”

“If I am in you and you are in me / Then it can be that I the slave am master of you.”

Sontag was right.