A Long Time On The Colorado Plateau

What happened there anyway?

Anasazi,

Anasazi,

tucked up in clefts in the cliffs

growing strict fields of corn and beans

sinking deeper and deeper in earth

up to your hips in Gods. . . .

–Gary Snyder

They are long gone, of course, eight centuries gone, but I always think they still own those crooked canyons and sunny alcoves where they built in sandstone and wrote on walls and signed their strange writs with hand prints. After the summer heat we drove to the Colorado Plateau looking for the goners, the absentee owners. We walked their intermittent ways in the sun and sat and read or talked by the lantern in the moon. Like good journalists and good tourists we came back with stories and pictures. There was a house on fire.

As if something still raged. As if it were telling us something.

A convenient center of this dry region is the Four Corners point where four rectilinear states meet. The sand-laden San Juan River lies across the center like a snake in the sun. Pat and I started at a place she found, The Kelly Place in McElmo canyon west of Cortez, CO., where Sleeping Ute Mountain looms. The green little country bed and breakfast has a small campground where we were T&B guests – tent and breakfast.

The southern boundary of the Canyons of the Ancients National Monument was a three-minute walk from our picnic table under an apple tree. Another 20 minutes and we were on the rough circuit trail of this relatively new park. The BLM has a creative policy here of letting you discover the Ancients (new word for the Anasazi) by yourself. No maps, no signs, not even names to mark most of the modest cliff houses.

I am not Lonely Planet, but because the Colorado Plateau is an undeclared national treasure let me say where else we walked in those weeks of October 2014: Chaco Culture National Historical Park, the Grand Gulch primitive area, the Paria wilderness, and the national monuments called Canyon de Chelly, Natural Bridges, Hovenweep, and Escalante. We were already quite familiar with the others here: Antelope Canyon, Navajo National Monument, Canyonlands National Park and Mesa Verde National Park.

We meandered like the San Juan and entertained mystery-writer questions:

Who were they? What happened here? Where did they come from?

Who They Were

In the beginning they were hunter-gatherers, anthropology says. Their traces are heavy projectile points, sealed corn caches, seasonal pit houses, and baskets, beautiful baskets. And so anthropology classifies them as Basketmakers. Eventually they became agrarian – settling down, planting their strict rows. Heavy pottery replaced light baskets. Pit houses became kivas, and year-round surface houses became more and more complex (and fatal, I will say later). These are classified as the Ancestral Pueblo people.

In the beginning they were hunter-gatherers, anthropology says. Their traces are heavy projectile points, sealed corn caches, seasonal pit houses, and baskets, beautiful baskets. And so anthropology classifies them as Basketmakers. Eventually they became agrarian – settling down, planting their strict rows. Heavy pottery replaced light baskets. Pit houses became kivas, and year-round surface houses became more and more complex (and fatal, I will say later). These are classified as the Ancestral Pueblo people.

They began laying up multi-room complexes in the 800’s. Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon in northwest New Mexico is the greatest of these houses. It grew to about 700 small rooms laid out in a D-ring backed against a high sandstone cliff. Direct sunlight swept the arc, and there were 40 kivas. Uncovered now, they look like craters of the moon.

In th e morning you can hear a chorus of tapping, hard rocks chipping soft rocks. The workers pass dressed stones to The Mason, who lines a course on the veneer wall and levels each stone with stone shimmies and taps each stone true and plum and stands back with an expert eye and nods in satisfaction that this work will last a long time. The workers do not look up at the priestly architect, a silent watcher on a threshhold. He sights along the wall. He knows true north. He calculates a future window that will frame the low winter sun when it begins returning. He knows the pendulum of the sun. He knows the pendulum of the moon.

e morning you can hear a chorus of tapping, hard rocks chipping soft rocks. The workers pass dressed stones to The Mason, who lines a course on the veneer wall and levels each stone with stone shimmies and taps each stone true and plum and stands back with an expert eye and nods in satisfaction that this work will last a long time. The workers do not look up at the priestly architect, a silent watcher on a threshhold. He sights along the wall. He knows true north. He calculates a future window that will frame the low winter sun when it begins returning. He knows the pendulum of the sun. He knows the pendulum of the moon.

They were not up to their hips in warriors, but there is evidence of empire. At least part of it was governed from Chaco Canyon, where the stacked great houses astonish tourists who have driven 20 or 30 miles on bad roads to be astonished. An ancient raised road bed that can be verified from space goes north obsessively straight from the rim above Pueblo Bonito through Pueblo Alto and then 30 miles to Aztec Ruin on the San Juan River. Pueblo Alto was built from 1020 to 1060, at the height of the empire. If you stand at the south entrance of Casa Rinconada, the great kiva associated with Pueblo Bonito, you can site through the north entrance to the lump of Pueblo Alto on the horizon. No big deal to line everything up with Polaris, you say. Except the North Star was not at true north back then. One archeologist says Chaco Canyon is 800 miles in a true north line from Casa Grande in Chihuahua.

They were not up to their hips in warriors, but there is evidence of empire. At least part of it was governed from Chaco Canyon, where the stacked great houses astonish tourists who have driven 20 or 30 miles on bad roads to be astonished. An ancient raised road bed that can be verified from space goes north obsessively straight from the rim above Pueblo Bonito through Pueblo Alto and then 30 miles to Aztec Ruin on the San Juan River. Pueblo Alto was built from 1020 to 1060, at the height of the empire. If you stand at the south entrance of Casa Rinconada, the great kiva associated with Pueblo Bonito, you can site through the north entrance to the lump of Pueblo Alto on the horizon. No big deal to line everything up with Polaris, you say. Except the North Star was not at true north back then. One archeologist says Chaco Canyon is 800 miles in a true north line from Casa Grande in Chihuahua.

Some who make the Anasazi their life’s work have projected straight roads in all directions, like spokes from the hub of Chaco Canyon, based on apparent segments. Ruins dot the “highways,” and these outliers have the same kind of houses and kivas. Some, at Hovenweep especially, have watchtowers. And along the North Highway, according to the writer Craig Childs, who has walked this line, there are regularly spaced high places in a line of sight. Watchmounds.

Some who make the Anasazi their life’s work have projected straight roads in all directions, like spokes from the hub of Chaco Canyon, based on apparent segments. Ruins dot the “highways,” and these outliers have the same kind of houses and kivas. Some, at Hovenweep especially, have watchtowers. And along the North Highway, according to the writer Craig Childs, who has walked this line, there are regularly spaced high places in a line of sight. Watchmounds.

The watchers wait for signals – relays of flashes from the holy seat of government, fires in the night saying, Now! Now the sun is beginning its return. Now the sun is equal, so plant. And now, the end. Now the priests are dead. Now the fire!

One frozen January morning a few years ago at Mesa Verde a ranger took us down the rungs of a lashed ladder in a shaft of light into a kiva. Inside as our eyes began to see we grew warm and felt refuge from the wind chill.

This refuge,  this gathering of kindred souls, our society’s kiva. We eat roasted pinon nuts by the kiva fire. The taste of those sweet nourishing kernels. The stars visible in the kiva hatchway. Cracking pine nuts and listening to elders. A place of patient talk and consensus. Shelter.

this gathering of kindred souls, our society’s kiva. We eat roasted pinon nuts by the kiva fire. The taste of those sweet nourishing kernels. The stars visible in the kiva hatchway. Cracking pine nuts and listening to elders. A place of patient talk and consensus. Shelter.

If anthropology is divided between the archeological and the ethnological, the kiva experience that January was on the ethno side. The ranger hardly said a thing except to remark that we could do this because we were six. In the summer we would be many, 200 or more. In the summer, the large groups listen to talks about corn and beans and hunting and water and tree rings, not religious experience.

That’s OK. It’s scientific. The founder of American anthropology, Franz Boas of Columbia University, was a gatherer of material evidence. He went to the Canadian arctic and produced an exhaustive study of Inuit tools and their uses. The early anthropologists at Chaco Canyon also were materialists. They gathered things and shipped them east by rail in wood-stave barrels. They reconstructed the broken walls.

The later professionals swept up the remnant pieces and dumped them near their digs. The dumps yield pot shards even now, though the pieces, usually white with black geometric lines or incised gray, have gotten harder to find.

Fifty years ago the shards were plentiful around Pueblo Bonito. But tourists scavenged them — unlawfully. Now people pick them up and arrange them on flat rocks where they were found for others to appreciate. It’s like catch and release trout fishing. Pat loves the pot shards more than the stone walls. Most women are drawn to them. They were made by women, by the hands and minds of women instructed by women. On the incised pieces you can see how their fingers worked.

At Chaco there were about 200,000 timbers. The lintels and vigas that survived the campfires of the early investigators are probably from mountains 50 miles away, assuming that the canyon was treeless as it is now. Scanning the tree-ring code, experts determined that construction abruptly ended at Chaco in 1117, at the onset of a 50-year drought.

Long ago I took a long hot horseback ride with Tova to Keet Seel in the Kayenta area. Our Navajo guide, a silent girl in her teens, stayed with the horses while we climbed up a high shaky ladder to the incredible, unreconstructed ruins. Beside a bin half full of finger-length corn cobs and a metate for grinding, I saw a flat stone with four deep stains the size of pancakes.

Long ago I took a long hot horseback ride with Tova to Keet Seel in the Kayenta area. Our Navajo guide, a silent girl in her teens, stayed with the horses while we climbed up a high shaky ladder to the incredible, unreconstructed ruins. Beside a bin half full of finger-length corn cobs and a metate for grinding, I saw a flat stone with four deep stains the size of pancakes.

She pours perfect circles of cornmeal batter. They hiss on the hot stone. She puts another stick on the precious coals. A man smells the cakes and climbs down from his work on a roof. She calls to some small children who have been scampering up and down the rocks. A girl climbs the main ladder with a pot of water on her head. A family gathers in the morning.

Years later the stone was on exhibit in a museum

I never understood how the Anasazi, usually shown bare and brown in dioramas, kept warm – it’s cold half the year in northwest New Mexico – until a ranger at Chaco showed us a piece of a turkey-feather blanket. Replicated by a Pueblo craftsman, it was two inches thick. It was warmer than my down vest.

A mother tucks her children under a soft blanket, soft and warm on the dirt floor. The rock walls are still warm. It is the darkest time. But there is no need for a fire in this cell.

The Anasazi domesticated turkeys. The bones in middens are evidence. In the sixties I knew Lyndon Hargrave, a bird-bone expert who ended his days on the faculty at Prescott College in Arizona despite his lack of graduate credentials. He could identify almost any bird, including prehistoric species, from a fragment of bone, matching it with samples in his taxonomic collection from University of Northern Arizona digs he had worked on beginning in the 1930’s.

Perhaps Hargrave’s most important publication was about scarlet macaws. He found 34 of them ceremoniously buried in Chaco Canyon – 30 at Pueblo Bonito and four within half a mile of it. All but nine were newly fledged, meaning they were a year old at the time of unnatural death, and the rest were adolescents except for one very old macaw. These parrots can live to be a hundred. They are semi-tropical birds. Their nearest habitat is southeast coastal Mexico. The implication was the colorful birds were imported at great expense for sacrificial rituals every spring.

The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss hoped future scientists, recognizing universal patterns of culture, will publish the anthropological equivalent of Mendeleev’s periodic table in chemistry. If so, then obsessed workers like Hargrave will be the equivalent of the much abused medieval alchemists, who prepared the facts for chemistry. Science.

On the other hand, the American anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote that anthropology is “not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning.” And so his major work is “The Interpretation of Cultures,” with an implied reference to Freud’s “The Interpretation of Dreams.” Geertz represents the ethno-school, those who find meaning in a kiva on a cold January morning.

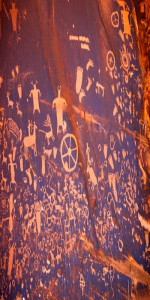

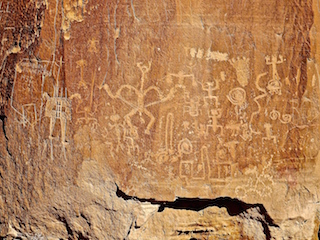

The interpretation of Anasazi culture also can grow out of careful reading of their literature. I know. They had no written language by our definition. But they did leave a library of scratched, pecked and painted figures. Many could be precursors of writing. Consider Chinese. The 214 classic characters called radicals began as sketches of primary things like your head or hand or a man or a mountain. Creative combinations of radicals and other characters representing meaning or sounds became words. Man plus mountain equals hermit. Tao, the Way, is the sign of a foot halted as at a crossroads plus a head. Think about it. The character for a Taoist priest is Tao plus noble knight.

Southwest rock art specialist Sally Cole shows, in her book “Legacy On Stone,” that the Anasazi depicted their world. There are big-horn sheep, deer, bears, cougars, coyotes, birds, insects, snakes, frogs, plants and abstract signs like circles, spirals or steps. The rock art we have seen does not suggest simply sketches. Often, it seems to me, the primary characteristic of an animal is exagerated. For example: a cougar’s front claws, a sheep’s curled horns, a snake’s fangs.

Which brings us to the subjective nature of the figures the professionals call anthropomorphs. Stickmen, lizardmen, and such. They are manlike, some even with testicles, some with menstrual aprons, a few with phalluses and a few bearing upside down tiny A-morphs in their x-ray bellies. Cole saw tears and smiles on some of their faces. She saw fighting and sexuality.

Similar to the cougars with claws big as rakes or sheep with spirals big as the sun, some A-morphs have supersized hands hung down from shoulders as broad as padded football players. The out-of-proportion hands have five careful fingers (altho Tony Hillerman built a novel out of some with six fingers). This was not our kind of art. It’s like they were on to something. I mean, neurologists have drawn functional pictures of the “homunculus” of our brains that have similar distortions. This is based on research with very sensitive probes. And in these drawings the hands predominate on the right and left. That is, the location of the brain’s left and right centers of manual dexterity are larger and more complex than most other parts of the anatomy.

The Anasazi also printed or traced their hands on rock walls. Outstanding places like the great arch in Grand Gulch are marked with dozens of hands stamped with red pigment. Sometimes they are in symmetrical pairs, sometimes child-size, but most often they are single adult hands at what would have been eye level for short adults. And I have seen a baby footprint. Bear in mind the Anasazi had no math, so the hand prints might have been a counting method or signatures or both.

How many men? That many, see? On the wall. See there, remember? We were here. I and thou. We offered things and  now they are gone. They are gone. But our hands on the wall will last a long time. Longer than we and even our hearts.

now they are gone. They are gone. But our hands on the wall will last a long time. Longer than we and even our hearts.

The experts agree that the A-morphs are beyond human. Their bodies are triangular or stretched long. Their heads are sometimes rectilinear. Most of them show horns or antennae that do not seem to be removable like decorations on hats. Some heads are in swirls of birds or shooting stars. These A-morphs with headdresses must have been religious authorities.

That Chinese character unified with the sign of the extended foot to make Taos, the one translated as head or chief was, according to one character book, “originally a picture of a man with horns or some big headdress.” This was on the other side of the world.

What Happened Here

Like those figures on the walls, interpretations of Anasazi culture are subjective. Like dream work, culture work often carries a contemporary message. In the 1980’s the message attached to the Anasazi often was ecological – the idea that they ruined their environment because they did not think ahead about climate change. This is still a profound message. But Craig Childs, a diligent journalistic researcher, proposes that the Colorado Plateau actually has not changed much since the flourishing of the Anasazi. He discredits the idea that the abandonment (and he proposes there was no sudden exodus) was provoked by drought and depleted soil.

In opposition, Jared Diamond says in his bestseller “Collapse” that deforestation was a cause of the abandonment. Ancient pack rat middens in Chaco Canyon contain things like pinyon and juniper nuts, berries, and needles, he writes. And now the nearest tree an impossibly long scamper away, for a rat. Maybe both Diamond and Childs are right, meeting in middle ground, because marginal environmental differences like a tree every mile instead of no tree anywhere do matter – as the difference of one or two degrees in human temperature, the difference of one or two tenths of a second in the speed of a rabbit chased by a coyote. Felling a tree for firewood is, or ought to be, a cataclysmic event if it’s the last tree, says Diamond. Boundary conditions are where the meanings are.

Did the baleful fire also have a human face? Christy Turner of Arizona State said there were three dozen instances involving 300 victims of Anasazi cannibalism. Childs asserts those who dug up these facts suppressed them in the interest of the Peaceful Indian story. He talks of defiled hearths, skulls opened for brains, pot-boiled bones, a load of shit in the exact center of a vandalized kiva, a room where seven were murdered and eaten. Maybe today’s news watchers would define these instances as family fights. Maybe the small flares of violence were not war by our definition. No villages burned down, no skeletons in the streets as at Casa Grande in Chihuahua. So if the enemy would have been familiar, the baleful fire would have come from within. Even so, the sporadic psychopathic violence would have been no less fearsome than war. News watchers know that domestic fear – the mass public shootings, the family massacres coming out of nowhere.

Terrifying violence itself motivates people to move away. In groups. So that would be an explanation of the abandonment. But what explains the unnatural violence itself? A University of New Mexico professor, Joseph Tainter, proposed that Chaco society was destroyed by its own complexity, and he itemized the decline and fall of dozens of historical empires to help make the point that complexity perpetuates itself and feeds on itself in an unsustainable process. In the end, vital resources are so expensive that the society cannot revert to its former rational simplicity. (Think: American health care, Pentagon.)

Whatever the causes that emptied the Four Corners region by 1350 or so, the Anasazi did not simply die and bury themselves. (Among the mysteries is why so few burial sites have been found – not yet – in a region that was as populated then as now.) They went south and east, replacing monumental stone with humble adobe houses by rivers or on mesas in New Mexico and northern Arizona. The institutional architecture of Chaco expressing the power of a religious empire was abandoned. There was a breakup, a return. The Anasazi emerged with an outwardly simpler way of life in nicer places.

Perhaps what saved the culture was the solidarity of kiva societies. Pueblos today still have plazas with kivas, even if the informal architecture is based on sun-baked bricks not dressed stones and their solar orientation is not so strict. In public ceremonies, different groups of dancers emerge from kivas and return to kivas for rest. The atmosphere of the seasonal ceremonies is peace. They are an intelligently peaceful people, as they might have been in the very beginning. I speak only as a tourist.

When the Spanish came colonizing and slashing at the bloody opening of the 1600’s there were 40,000 Pueblo people living in agrarian equilibrium, if not enduring peace (they bickered territorially). “The large number of scattered villages, averaging no more than several hundred people in each, says that the Indians had mastered an important principle,” New Mexico historian Marc Simmons wrote. “They might have learned that restricting population density prevented an overtaxing of natural resources.” By the time they were thoroughly Christianized, they numbered only 15,000.

![]() But their ancient religion persisted underground. The friars raided kivas and destroyed the masks and costumes for kachina ceremonies. At the same time their own Inquisition searched for crypto Jews, who escaped to the new world. (In New Mexico, the enchanted land of covert religion, authorities continued the tradition with the persecution of mystic users of herbs and buttons in the American sixties.)

But their ancient religion persisted underground. The friars raided kivas and destroyed the masks and costumes for kachina ceremonies. At the same time their own Inquisition searched for crypto Jews, who escaped to the new world. (In New Mexico, the enchanted land of covert religion, authorities continued the tradition with the persecution of mystic users of herbs and buttons in the American sixties.)

After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 the Spanish learned accommodation. The Taco Bell fronts of adobe churches cast long winter shadows on plazas cratered with kivas. And then came the Americans, with soldiers in 1846, followed by traders, followed by Jewish merchants, followed by exotica-loving art colonists. The artists of Taos and Santa Fe loved to go to Indian dances. And the rich and influential Mabel Dodge married Tony Lujan, a Taos Indian. The union was celebrated internationally. Paul Frank, a hotel-chain manager who retired to Santa Fe at the time, observed years later with some cynical humor that if Tony Lujan happened to stand on a roof wrapped in a white blanket, “then there would be pictures all over of Tony standing on his roof watching the sun go down. Tony enjoyed it. It’s just Tony standing on his roof, but it had significance all over and back in New York.”

D. H. Lawrence, who lived and wrote on a mountain north of Taos for a summer and a winter in the 1920’s, saw in the Pueblos the most religious people still living.

“It was a vast old religion, greater than anything we know: more starkly and nakedly religious. There is no God, no concept of God. All is God. But it is not the pantheism we are accustomed to, which expresses itself as ‘God is everywhere, God is in everything.’ In the oldest religion, everything is alive, not supernaturally but naturally alive.”

C. G. Jung visited Taos Pueblo twice during this era of art and letters and received a comparable religious insight, as a psychiatrist. In his autobiography decades later he remembered a conversation with a Taos elder who, pointing at the sun, said, “How can there be another god? Nothing can be without the sun. . . . The sun is God, everyone can see that.” And another, sidling up to him beside the brook that runs from a high basin through the pueblo, said, “Do you not think that all life comes from the mountain?” Jung flashed on the holiness of mountains in the Old Testament. The great syncretic thinker was impressed by the healthy, direct and “overpowering” influence of this natural religion. Lawrence called it “empowering.”

Jung’s visit to Taos Pueblo verified his pathology of patients who seemed to be missing souls. He recalled a comment about the white tourists by his first informant there:

Their eyes have a staring expression; they are always seeking something. What are they seeking? The whites always want something, they are always uneasy and restless. We do not know what they want, we do not understand them. We think that they are mad.’

The poet Robinson Jeffers pictured them:

Pilgrims from civilization, anxiously seeking beauty, religion, poetry

pilgrims from a vacuum.

In 1976 as an AP writer I covered a federal court trial that involved the continued religious tradition at Taos Pueblo. Some women householders sued the all-male tribal council, claiming discrimination because they were denied electricity. The famous tiered and laddered structures with rooms owned but not usually lived in by tribal members are not electrified, but the council had allowed electricity outside the west walls while prohibiting it on the east where the plaintiffs lived.

The sole defense witness before U.S. District Judge Edwin L. Mechem was Juan Jesus Romero, a very old man with thick glasses who leaned on a green staff for support. “I am the spiritual head of the Taos Pueblo Indians,” he said in translation from Tiwa. “I tell my people how to conduct their religion.” He said electricity causes him pain. “Everything originates in the east,” said the very old man who lives alone in a small house near the creek that arises in the east. That side of the pueblo “has uses every person of Taos decent knows about,” he said.

I wanted to talk to him, to ask him about the Anasazi and the pendulum of the sun and the kivas of the moon and whether kachinas were real or just masked men. I wanted to ask if dwellings faced the sun for spiritual as well as physical warmth and if he knew the focus of Pueblo Bonito. And suddenly there he was! He was next to me during a recess in the trial in the men’s room of the Santa Fe federal court house, standing with his staff leaning against the tiled wall. I kept silent as usual at urinals, recognizing the inappropriateness of talk to a peeing holy man.

From a distance in the court room I imagined that his staff was deliberately green, like nature, and that it was a talisman like the canes Abraham Lincoln sent to each Pueblo as a seal in recognition their protected status as “nations within a nation,” in the words of Justice Marshall three decades earlier. It was just an old cutoff broomstick with flaking green paint.

Judge Mechem, in an opinion upholding Indian sovereignty, dismissed the women’s complaint on the basis that he had no jurisdiction, that government had no business prying into this ancient religion.

It is not my business either, but as I said, I speak as an enthused tourist.

So, I speculated upon the “supernova” picture on a high protected wall at Chaco. The official interpretation is this is like journalism: a sort of graphic report of the supernova of 1043 known to have been visible there. But this requires a reading that the middle figure is a super bright star, not the sun. the experts say the sun is usually depicted instead as concentric circles or even left or right spirals. Still, invoking tourist rights, I prefer an interpretation of meaning, not fact. To me this picture represents the inclusive but not pantheistic trinity of a natural desert religion: sun-moon-man.

Where Did They Come From?

Nobody dares to speculate professionally on the origins of the Anasazi beyond the soft boundaries of the term “archaic people” originating 12,000 years ago. It seems they just arose in the unknown reaches of time and arrived on the Colorado Plateau as “Basketmakers,” hunter-gatherers who made baskets, not pots, and camped in seasonal pit houses. They planted corn where they stopped and stored the harvested cobs in rat-proof cists. They replaced the leveraged speer-throwing atlatl with the bow and arrow.

As with all the Anasazi, not much is known or said about religious practice except that that kivas must have been sacred places and the horned and hatted A-morphs were not strictly human. And the Basketmakers, some of them, revered human heads. There are pictures of head skins (or masks) carried on sticks. Some figures of severed heads (or masks) are, in Cole’s delicate phrasing, pendants because they seem to have carrying loops. The archeologist Alfred Kidder found a “trophy” made of the skin of a human head in the burial of a young woman with a baby tied in its woven carrier. Segments of a cord indicated the head was attached to the woman like a necklace. Cole saw significant similarity between the decoration and hair-bobs of this trophy head and a painting called the Green Mask in Grand Gulch. Long ago we camped on the flats near the gulch where the unusually bright painting looks down from high in an alcove. The site was a little eerie because it was where Richard Wetherill, the cowboy archeologist, in the 1890’s dug into some ancient graves. He was the first to indulge in the practice that so offends Native Americans.

Around 800 CE the Basketmakers abandoned their backpacking ways and settled down, becoming predominantly agrarian people with some sort of religion. Ancestral Pueblo population boomed. It was my frequent speculation, by lantern light, that they secularized as they settled down. Their A-morphs on the rocks became smaller and less embellished – more human. It was not a funereal culture. Several royal graves with hundreds of priceless artifacts were dug up at Chaco, but there is a mysterious absence of common graves.

And so arose the empire of Chaco with its monumental construction, and so it declined and fell in the 1100’s, and so there was a scattering and a less monumental construction in the cliffs of Mesa Verde and Kayenta, and so there was another scattering in the late 1300’s to nicer places, and so the people endured acculturation by the Spanish and then the Americans, and so now there is a scattering of resort hotels and glittering “Indian” casinos.

But, again, where did the Anasazi come from? I don’t mean the Bering Strait of geography or the sipapu of mythology. I mean where did their souls come from before they were, if you please – possibly and not in any way generally – head hunters and cannibals? I know. The image ought to be suppressed in tourist literature. It can infiltrate a car camp with dark shadows as soon as the lantern is turned off.

What is at the heart of the Anasazi? Out in the southern Utah desert at the end of a long dirt road where the world is in silent meditation a watchful National Park ranger who said she refused promotions to stay right here allowed us some years ago to walk a white-dust trail, a half hour down (and an hour back up) to the floor of a canyon where willows were returning due to the end of cattle grazing.

So silent. You look around. And then, as if through a distant doorway in a vast museum, you see the masterpiece: the Holy Ghost Panel, in a natural frame of sheltered sandstone. The images are artistically larger than a man in the mode of later Western sculpture, but one is king.

This is the work that gave the “Barrier Canyon style” its name. It may be 2500 years old. Cole knew of only 30 sites of this kind, all within the Colorado Plateau.

The predominant figure is about seven feet tall. The ethereal thing about them all is they have no arms or legs. These and similar A-morphs appear to be “wrapped,” Cole writes, suggesting mummies. I wonder about the meaning of her description.

If you guys are dead but upright, then you are arisen. You are reborn. Twice born. Where are your arms and legs? No matter, I guess. You have no need now to walk as humans, no need to manipulate the ten-thousand things. You are bound but unbound. You are quiet at last. You ascend. You do not scare me, not any more.

Polly Schaafsma, in her encyclopedic “Indian Rock Art of the Southwest,” compares the Barrier figures with the later more realistic Anasazi images of humans. She wrote:

Considering the elaborate headgear and other paraphernalia and the occasional depiction of masks, I feel that the Barrier anthropomorphs not only had ceremonial import but they exceeded the realm of the ordinary: they were probably representations either of supernatural beings themselves or of shamans. Images such as these may have been thought to contain the soul force of the beings they represent.

In and around these holy images are handprints of apparent supplicants, she says, adding that modern Pueblo people impress their painted hands at sacred places so that, perhaps, they will not be forgotten.

The 1983 film “Koyaanisqatsi” by Godfrey Reggio of Santa Fe depicts our hurried, disquieted technological life with high speed aerial film clips integrated with the score by Phillip Glass, his first for a film. The frenetic poetry of image and sound expresses our “crazy life,” which is one translation of koyaanisqatsi, a Hopi word. Others: life in turmoil, life out of balance, life disintegrating. Godfrey’s film is hard to date. The high, distant, time-lapse shots of how we live – traffic on freeways, swarms of rushing people – are ageless. The views are usually too distant, too fast, for fashion judgments.

We begin in music and light. We see the Holy Ghost Panel in its stillness, broken by the sprung rhythm of the music and the light of a prolonged fire. The fire becomes the tail of a rocket lifting off, escaping. We are battered with time-lapse sequences of hurrying and destruction. And then, a kind of relief, a crescendo of fire. And at long last we return to the beginning, the stillness again of these canyon images. Yes, this is how they must have been in the beginning, the Basketmakers of the Anasazi. Their icons were wrapped beings with no motion, totally still within, arisen.

And So. . .

We came back with stories and pictures from a dry unforested environment of earth and air that looks eternal. The natural varnish in which the Anasazi carved their literature is an accumulation of millennia. The desert is effective. In 1992 I was in a group whose leader took us to an undisturbed kiva hidden in a dry rincon in Grand Gulch. The cover was intact and a ladder stuck up from a hatchway in the middle. In front of the kiva was a perfectly dry piece of paper weighted down by a small rock. It was an old BLM ranger’s note saying please leave this place alone. It was signed and dated 1973.

The desert preserves. But what if the climate changes? Perennially dry canyon walls are streaked with pouroff water stains. Water-smoothed logs are jammed 30 feet up in dry slot canyons. The Anasazi knew about torrents. That is one reason, I suppose, for their dwellings high on cliffs. What if the hundred-year floods become annual?

So, hurry. We came back with our journalism, and people might say, “House on Fire. Gotta go there. Gotta get pictures and come home and hit “save.” This is how tourism works. It’s a powerful media-driven industry. A stack of dark and light sandstone in narrow layers called The Wave is so popular, despite the unsettling long waterless desert trail to this photo op, that the BLM chooses visitors by competitive lottery.

I mean, “Bucket list” has entered our language as a philosophy of life. Never mind that the movie in which Jack Nicholson and Morgan Freeman are dying of cancer is a comedy. Roger Ebert, dying of cancer, said its writer “must be very optimistic indeed if he doesn’t know that there is nothing like a serious illness to bring you to the end of sit-com clichés.” The metaphor here is a bucket full of many busy things to do, under the urgency of death. There is a familiar bucket image in Soto Zen literature. Its context is Zen meditation – just sitting – when suddenly the bottom of the bucket drops out, releasing all those “should’s” and “gotta’s” and “supposed to’s.” A patriarch in medieval China said, “People with the bottom of the bucket fallen out immediately find total trust.”

Still, whatever the psychology, tourism might save the “geography of hope” (Stegner, not Obama). Because out on the Colorado Plateau are drillers and strip-miners, pot hunters and polygamist ranchers and general government haters seeking their fortunes in America’s “empty country.” They are being crowded out, maybe, by tourist developers. Next problem: the geography of hope is filling up with tourism. Example: the Sun Dagger is a slim periodic sunrise projection on the southeast face of Fajada butte at Chaco Canyon. The constructed effect was discovered in 1977. It recorded the summer and winter solstices and the two equinoxes on spirals carefully chipped in the rock. People rushed to see it. The tourist traffic altered the two standing rocks that made the projection. Now the clock is off. And the site had to be closed.

Or take Monument Valley, no longer the remote pure-land backdrop of John Ford’s Westerns. The airstrip at Golding’s is active with executive jets. Or take the Antelope Canyon of coffee-table books. It can get crowded, even at a $50 a ticket ($80 for photography tours). OK. These places belong to the Navajo Nation, and the traffic is their business. Other tribes justifiably profit from other attractions, but the helicopters that constantly cross the Grand Canyon at the Hermit Trail corridor, drowning the music of a desert bighorn sheep making his way up the rocks, are not Indian. A gondola tram is proposed further up. And of course there is Glen Canyon Dam, with its propagandistic visitor center and all the house boats and those inputs stranded a mile from the receding lake.

We took the middle way, mostly. We liked The Kelly Place with easy access to the Canyons of the Ancients, where the BLM lets you discover everything for yourself. You can do it this way. But stay on the trails. And never pocket pot shards. They bring bad luck.

Perhaps, the non-destructive new anthropologists will fulfill the hope of Lévi-Strauss (finding a law of societies and how they crumble). Or perhaps another anthropologist like Geertz will write a marvelous essay interpreting the mysteries anew. I hope for the geography of hope. Because the house on fire is our house.

Hi Larry,

Great piece. Thanks.

My theory is the Anasazi left because of sustained drought and disease, crop or human. Another precipitating factor ( no pun intended) was a change in leadership. Somebody had a vision that staying put would be detrimental to the tribe and led them to “the promised land.” So many human stories are so universal that one or more of the above probably hold true for the Anasazi as well.