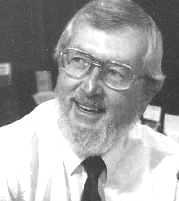

Ernie Mills: The Voice From Santa Fe Goes Off The Air

Memorial service planned for St. Patrick’s Day at the Capitol

If you’ve ever been a name in a major news story, it will lead your obituary. That’s the way the news goes, especially when a journalist dies. And most of the stories on the death of Ernie Mills, a trusted voice from Santa Fe for thousands of New Mexicans for 45 years, led with his role in talking down the murderous 1980 State Penitentiary riot.

A memorial service is being planned for the State Capitol at 1:00p.m. on March 17, St. Patrick’s Day. (He was Irish-Catholic by upbringing). Arrangements for burial of his ashes have not been announced.

Ernie was the man, the only man, who stood inside the fences and, hour after hour in the smoke and the cold, negotiated with the prisoners for the lives of the guard hostages. He wanted to write a book about the experience, but his work was always in the way. His daily “Dateline New Mexico” and other broadcasts on a radio network that once included 30 stations, plus his weekly public television show, came first.

Age did not slow him down. In four decades of broadcasting and two decades of print journalism before that, Ernie probably never missed a deadline. Even the respiratory problems that put him in the hospital on Feb. 18 did not slow him down, at first. Lorene, his wife, told me he was planning broadcasts until he had to be put on life support for a pneumonia-like ailment of yet undetermined cause.

When it became evident that Ernie was dying, Lorene called in a few old friends — Ernie’s four children were already there — whose voices she thought he would want to hear. Gov. Bill Richardson was among those who came to the intensive care unit to say goodbye. Ernie breathed peacefully another day, and at 10:30 a.m. on Feb. 26, the lines on the monitors all went flat. He was 76.

Ol’ Ern, as many called him after he came back from Vietnam with a graying beard, never wrote that prison riot book. He was too close to the material. Perhaps it’s just as well. The Aryan gang leaders who went through the pen torturing and murdering the weak and the snitches don’t even deserve to be named.

At one point in the hostage crisis they had a body brought out on a stretcher for Ernie to see. This was no hostage being set free. This was the mutilated corpse of a black prisoner. His decapitated head had been stuffed between his legs. Felix Rodriguez, the deputy warden, had warned Ernie they would try to shock him. He knew he could not react, and he never blinked. The negotiations continued, and the guards — some of the eight were hiding and not hostages — got out before the prison was stormed and retaken.

Rodriguez had come to Ernie with the request from some of the prisoners who said they wanted to talk, but only to Ernie Mills. Rodriguez, despite varying titles over the years, was the man who ran the pen — from the inside. He used to walk through the corridors greeting prisoners by their first names and listening to their complaints personally.

So “Mr. Rod,” as I once heard an Anglo inmate call him, knew more than anyone the risk that Ernie would be taking. But he also knew Ernie would not hesitate. Rodriguez had him duck down in a car and drove him past the gang of news crews at the highway gate, past the National Guard along the prison road, up to the main tower. They walked to the first sliding steel gate. It opened. Ernie went in alone. It closed behind him. Then the other one.

Years later Ernie talked with a guard who said he watched him for hours through the scope on a rifle. Ernie thanked the sniper for the backup, but could not help observing that if he was in the scope he also was in the crosshairs.

Ernie was discouraged by the fast books and articles on the riot that seemed to glorify the rioters as if they had a civil rights cause and vilified Rodriguez as if he were a Southern sheriff. But that was the mood of the publishing business, stuck in the Sixties and wedded to old cliches. And it was the attitude of many in the national media, who tended to be totally lost in places like New Mexico. Any other point of view was a hard sell.

Ernie, who grew up poor in Brooklyn as the son of a widowed Irish Catholic nurse, knew where he stood politically — he called himself “a Hubert Humphrey liberal.” But he loved all politics, and most politicians interested him, no matter what their views. But with him, to reverse the old slogan, the political was personal. He focused on personalities, not dogma.

Vietnam, for example, divided the country politically, and Ernie was not for the nature and strategy of the war. But he went to Vietnam twice to cover New Mexico soldiers for the folks back home, sometimes under fire. He had to hole up in a bunker at Da Nang during one intensive fire fight. The broadcasts of his interviews drew a wide New Mexico audience, and some were even played on TV, audio only, with still pictures on the screen.

“I went over because I didn’t believe what I was seeing on national television,” he told Bill MacNeil of Journal North five years ago. “I saw young men who were scared and homesick, who weren’t just shooting at people, but helping build homes for the Vietnamese.” Nine of the soldiers he interviewed later died in the war.

Ernie, born in Pittsburgh, was a lifetime Steelers fan, and he got a kick out of socializing with Pittsburgh players who came to Santa Fe from time to time to visit their investments. He liked most sports and kept in shape through some invisible program that probably came down to working hard at what he loved. When the running craze hit the Santa Fe streets, Ernie used to watch the grim self-timing joggers on his way to work at sunrise and wonder why they weren’t smiling. Life is supposed to be fun, he often said.

Ernie Mills

When he was 18, just out of Bedford-Stuyvesant Boys High School in Brooklyn, he became a professional skater. He had fond memories of the life and the performances in Madison Square Garden. He travelled with one of the early revues called “Hats Off To Ice.” Ernie had a heart murmer, which he never mentioned until two years ago when a doctor told him it was time to have a long-delayed operation — insertion of a mechanical heart valve.

Specialists at Albuquerque Heart Hospital reassured him that the operation had been done thousands of times and was perfectly safe. “So if I die,” he told me a week before surgery. “I’ll really be pissed.”

Ernie’s first job in journalism was with the New York Herald Tribune beginning in 1949. He was assigned to the maritime beat. He was fascinated by everybody — the old pros on the paper who let him in to the press club, the gruff editors, the waterfront bosses. He once had to get a comment from one of them — Joe Bonano, I think — who did not like the story he was writing, but said he understood the news business. “You do your job, I’ll do mine,” the Mafia leader told him.

The story was an object lesson. It involved an ethic that Ernie respected, and having ethics and the courage to stick to them was the secret of getting along with Ernie Mills — although many politicians never caught on.

Ernie began college classes while he was a reporter. He graduated cum laude from Rutgers University 1955 with a degree in public administration. The next year he decided to move to the Southwest, and on his way to Phoenix he fell in love with Gallup, of all places, where he was hired by the Independent as managing editor. The paper’s motto, he said, was, “We cover Indian Country like a blanket.”

One day Hollywood producer Michael Todd, husband of Elizabeth Taylor, was killed in a crash of his executive jet near Grants, down the road from Gallup. One of Ernie’s proudest mementos was the front page of the New York Herald Tribune, his old paper, with his byline on the banner story of the crash. He had never led the Trib before.

Ernie moved to Santa Fe in 1958 and covered the capitol for the Albuquerque Journal, filing stories on an old teletype from an office he said was about the size of a closet with a window full of annoying pigeons. Maybe that’s what inspired his line: “A little birdie told me.” He left journalism in 1960 to do public relations and serve as press secretary to Gov. John Burroughs. In 1965 he began his broadcast career.

The late-blooming Rutgers graduate had a lifetime appreciation of education. He served on the board of regents of Western New Mexico University, received honorary doctorates from New Mexico State University and the College of the Southwest, and was lifetime honorary alumnus of Eastern New Mexico University.

Ernie’s home radio station was Santa Fe-based KSWV-AM, which is bilingual — Ernie used to say he was the minority worker there. In 1996 owners Selena and George Gonzales invited me to buy a ticket to a little gathering for Ernie, a testimonial dinner. Arriving at the Hotel Eldorado I thought, whoa, I must have the date wrong. The ballroom was packed with what appeared to be a major convention.

But it was only about 600 of Ernie’s closet friends, including both U.S. Senators, a Congressman and five former governors. The governors took turns on the stage doing Bruce King imitations. Bruce won the contest.

Ernie was not supposed to speak, but he took the rostrum to make a remark. He expressed his hope that the “meanness,” as he put it, which had overtaken politics and journalism would give way to understanding. With that, I should bring this column to an end. But I have a personal note.

On his next to last day, I sat alone with Ernie for a while in the intensive-care hospital room. He was already unconscious, it seemed, but many believe that hearing is the last sense to go. So I began recollecting stories out loud. As I remembered our contentious lunch tables at the Bull Ring in the old days with the late Bob Barth, I watched the heartline on the green monitor screen for reactions, and there might have been a bend in a wave or two streaming by.

I realized as I surveyed all the sensors and probes attached to Ernie’s

chest and muscular arms that I had never seen my old friend with his shirt off. He was a tough old guy.

I reminded him of the time he got a death threat. The voice on the telephone said he would be shot if he attended a certain political rally in West Las Vegas the next day.

What’d he do? Nothing, exept his job. He deliberately stood alone in the open space between the crowd and the platform, a perfect target, taking in the political speeches.

And now there was another death threat, a bad one. I knew Ernie was facing it as before: with courage and generosity of spirit, even if he was really pissed.