Politics and Potlatch

The anthropology of gifts: Warrior class of ancient India, First Nation people of British Columbia, Wine Cave dwellers of California

By LARRY JOSEPH CALLOWAY (C)

The Wine Cave War that livened up the Democrat presidential debate a week before Christmas 2019 was timely because it was the season of giving, and the issue was gifts by wealthy people to political campaigns.

News photos of the cool underground tasting room with its stone arches, crystal chandelier and long banquet table illustrated Elizabeth Warren’s claim that Pete Buttigieg had bonded with the billionaire cave dwellers while she by contrast was out among ordinary people doing “100,000 selfies” for free.

News photos of the cool underground tasting room with its stone arches, crystal chandelier and long banquet table illustrated Elizabeth Warren’s claim that Pete Buttigieg had bonded with the billionaire cave dwellers while she by contrast was out among ordinary people doing “100,000 selfies” for free.

In my career as a journalist there were many locked doors. I waited with guards or police for candidates — and once for the Dalai Lama in Santa Fe — to emerge from these money rituals. And I had seen enough fund-raising events to know that the strategy was to get people competing like bidders at an art auction, showing their wealth by conspicuous generosity. It’s as if people have a deep instinctive yearning for community and voluntary giving. Call it potlatch.

Anthropologists have popularized this First Nation word for massive giveaways among the original people of the northwest Pacific coast. It was first reported by Franz Boas, the founder of American anthropology. In an 1888 article he quoted a Kwakiutl leader in these words: “It is the great desire of every chief and even of every man to collect a large amount of property, and then to give a great potlatch, a feast in which all is distributed among his friends and, if possible, among neighboring tribes.” It was serious business and brought whole tribes together for feasting, song and dance.

The French anthropologist Marcel Mauss (1872-1950), whose book “The Gift” is still in print in various English translations, studied gift-giving in cultures worldwide. One of the earliest with a written record was the ancient culture of northern India. The Mahabharata, the Sanskrit epic dating from 400 BCE, “is the story of a gigantic potlatch,” Mauss wrote.

The French anthropologist Marcel Mauss (1872-1950), whose book “The Gift” is still in print in various English translations, studied gift-giving in cultures worldwide. One of the earliest with a written record was the ancient culture of northern India. The Mahabharata, the Sanskrit epic dating from 400 BCE, “is the story of a gigantic potlatch,” Mauss wrote.

The Mahabharata is loaded with mandatory gifting and payment of tributes, but the chapter that Mauss must have had in mind is the gambling sequence, which prefaces the war chronicled in the chapter called the Bhagavad Gita. He wrote, “In certain kinds of potlatch one must expend all that one has, keeping nothing back.” And, “Gambling is a form of potlatch and the gift system.”

So in a lavish hall, which is “a cry long and a cry wide,” the two factions of a noble warrior-class kinship gather. Yudhisthira, the king of the Pandava family is invited by the corrupt leader of the Kaurava family to play a “dicing game.” The rules are now unknown, but it is a game of skill, not chance. Yudhisthira cannot honorably refuse the invitation, even though he knows the Kauravas have substituted a player who is an expert cheater. In the first 10 rolls of the dice the Pandava king bets and loses everything moveable. He proudly glorifies each stake, but this first wave of lost personal property is actually just an accumulation of former tributes.

The king, ignoring the pleas of his family, next accepts the challenge to join in a second set of 10 dice rolls. This — in my opinion — goes beyond the common understanding of potlatch because the stakes are real property necessary for survival. And the outrageous game escalates until the king loses all his subjects (except Brahmins), then his four brothers, then himself — all into slavery — and on the final roll of the dice, the Pandavas lose their “wife,” avatar of the goddess Lakshmi. The Pandavas negotiate a settlement and are banished to the forest, without possessions.

My interpretation of the second set of 10 dice-rolls is that it is a metaphor of renunciation (or relinquishment), a familiar story in Eastern classics. A mighty noble “casts down” every possession and retires to the wilderness, and the forest dweller becomes enlightened. The Pandavas survive for 12 years, enduring taunts by the Kauravas. They emerge strong and skilled — and they win the ensuing war.

Mauss learned about potlatch by studying the Kwakiutl people of Vancouver Island and the mainland across Alert Bay and the channel. His critique was that potlatch was “a kind of monstrous product of the system of presents.” This echoed Boas, who dismissed it as excessive and a hindrance to family wealth. Canadian authorities shared this sentiment, and Canada outlawed potlatch.

In the winter of 1921 an Alert Bay native named Dan Cranmer organized an enormous secret potlatch on a remote island. The local Indian agent, W. M. Halliday, was informed and summoned the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The redcoat officers rode in, confiscated evidence, and took prisoners, who were promptly tried and found guilty. To stay out of prison, most signed away their rights to the confiscated items. Some 450 artifacts were given to major Canadian museums.

In the 1970’s a movement began imploring museums to return of these treasures. The final agreement kept them out of the hands of the families that claimed them, consigning them in equal portions to two museums on native reserves. The last of the items to be returned, in 2003, were 16 whose provenance went from the private collection of agent Halliday to the U.S. Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of the American Indian.

In the 1970’s a movement began imploring museums to return of these treasures. The final agreement kept them out of the hands of the families that claimed them, consigning them in equal portions to two museums on native reserves. The last of the items to be returned, in 2003, were 16 whose provenance went from the private collection of agent Halliday to the U.S. Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of the American Indian.

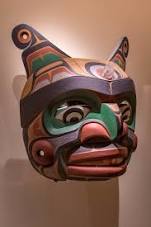

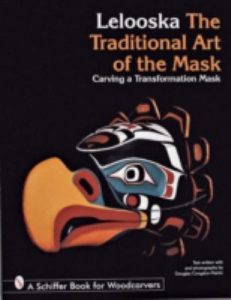

A wonderful modern-day anthropological writer, James Clifford, visited the Vancouver-Victoria area museums and reflected upon their exhibits in his book “Routes” (Harvard 1997) about the presentations of cultural tourism seen in his global travels. At the Kwakiutl Museum on Quadra Island and the U’mista Cultural Center on an island in Alert Bay he saw displays of painted cedar carvings — especially ceremonial masks.

At the U’mista (a Kwakiutl word describing the feeling of war prisoners who manage to return home safely) was a display text that tells a story reflecting the religious significance of masks. Some chiefs were arguing about the origin of humans. One said it was the sun that created their ancestors. Another said that was impossible — the sun never created even one man. The host at last said the truth is this: “It was the seagull who first became man by taking off his mask and turning into a man.” No, another said, it was the grizzly bear who took off his mask and became a man. Another disagreed. It was the thunderbird who took off his mask. I assume each chief was the head of a clan, as kinship groups are sometimes called.

The regalia as Clifford describes them include sacred artifacts that were not the personal property of the chiefs who gave and received them, but belonged to kinship groups. Mauss himself said in traditional societies “It is not individuals but collectives that impose obligations of exchange and contract upon each other.” (A word on obligations in a minute.)

Clifford’s heartfelt descriptions, however, are at odds with the potlatch views of the old anthropologists and Indian agents as he described them. “This central ceremony of the Northwest coast cultures was thought to be a ‘savage’ custom because of its dramatic dances and ‘excessive’ redistributions of wealth,” he wrote.

He quotes a placard in the U’mista: “We dance to celebrate life, to show we are grateful for all our treasures. We must dance to show our history, since our history is always passed on in songs and dances. It is very important to tell the stories in exactly the same way. We put our stories into songs and into dances so they will not change. They will be told the same way every time. We use theatre and impressive masks to tell our ancestor’s adventures so the people witnessing the dance will remember it.”

He quotes a placard in the U’mista: “We dance to celebrate life, to show we are grateful for all our treasures. We must dance to show our history, since our history is always passed on in songs and dances. It is very important to tell the stories in exactly the same way. We put our stories into songs and into dances so they will not change. They will be told the same way every time. We use theatre and impressive masks to tell our ancestor’s adventures so the people witnessing the dance will remember it.”

So, back to American political giving. They don’t dance in wine caves, so far as I know. But maybe they would like to. Street demonstrations, a different sort of cultural assembly, often do involve erratic dance and song. Confrontation with police has become ritualistic. Whatever, the money from large and small givers rolls in — $1.4 billion reported by Hillary Clinton and $900 million by Donald Trump in the last presidential campaign.

It is excessive. It is monstrous.

Money has become so important that 18 months before the next general election the Democratic National Committee was pawing through campaign chests to help pick participants in its debate shows, eventually eliminating minorities. Certainly volunteers are important, but the main objective this early in campaigns is money. Journalists “follow the money.”

Half the money goes to the media, who in turn rank candidates by money. Mauss died before the age of television, but his sentiment about deeper, remnant currents in modern culture is still valid. He said in summarizing the universal codes of gifting: “A considerable part of our morality and our lives themselves are still permeated with this same atmosphere of the gift, where obligation and liberty intermingle, Fortunately, everything is still not wholly categorized in terms of buying and selling.”

He found that among the cultural commonalities concerning gift codes worldwide are these: that a bond is created between giver and receiver requiring reciprocity, that a person who does not reciprocate is shamed, that charity is “wounding,” and that some gifts are “dangerous.”

Political campaigns would be wise to hire, among their expensive poll-obsessed consultants, a few people who took anthropology in college. It might produce surprising new winning strategies. For instance, concerning reciprocity most people actually don’t believe the claim that politicians are not obligated to their contributors, nor the media by their advertisers. And a politician who says he won’t reciprocate is silently shamed as untrustworthy.

So Buttigieg was smart, in his response to Warren’s effective attack, to avoid proclaiming he would not be influenced by the contributors in the wine cave. But his poor-boy defense was dangerous because it made him look wounded. At the same time, Warren’s claim that she was out there working hard for nothing did not seem genuine.

So Buttigieg was smart, in his response to Warren’s effective attack, to avoid proclaiming he would not be influenced by the contributors in the wine cave. But his poor-boy defense was dangerous because it made him look wounded. At the same time, Warren’s claim that she was out there working hard for nothing did not seem genuine.

Political success requires gifts. Hillary Clinton, after all, campaigned tirelessly on a theme that she was a hard worker who would work hard for everybody even at 3 a.m. Her opponent, Donald Trump, was a man who presented himself as a gifted (in several ways) genius for whom everything is easy — winning trade wars, getting Mexico to pay for a wall. The gift of evangelical support was reciprocated with judges, but now the evangelicals must counter-reciprocate. They will be shamed if they decline. The cycle goes on.

Mauss said that in the societies he studied the economy of private transactions — the art of deals — between individuals is hardly found. “It is not individuals but collectives that impose obligations of exchange and contract upon each other.” A current example: military aid to Ukraine certainly creates an obligation, but it is to the United States and not to the president personally.

I live in a community of spiritual centers where the main business is retreats and healing. And much of the subculture here communes with the past — the Ute Indians and others who passed through the San Luis Valley. We still have a newspaper, a healthy monthly, but it seldom mentions national or state politicians (they ignore us in return). People write about their griefs and grievances. And gratitudes. Some groups dance. Some sit in forgetfulness. There are forest dwellers everywhere.

Culture policing like the outlawing of potlatch happened all over the continent. The ghost dance was outlawed in the United States. As early as 1630, the Puritans banished Thomas Morton for erecting a maypole and dancing with the Indians. The culture police became genocidal when things also became economic, hindering the manifest destiny. There were massacres like at Wounded Knee or the Sandhills of southern Colorado. But the original people — called Native Americans here and First Nation people in Canada — and their ways of life have endured against overwhelming prejudice and Indian-head nickels.

Clifford wrote, “On the Northwest coast, as elsewhere, the economies and institutions of the modern nation-state have systematically exploited, repressed, and marginalized the traditional cultures of native peoples. Exploitation — substandard schools, inferior healthcare, poor job prospects — continues in many places. So does political resistance and the crucial resource of a strong, supple tradition.”